Hail, Rome!

Hail, Rome! The sun is bright,

the serpent perched on high

on bough that bears the apples light

whence you shall surely die.

And are you strong? O Mighty Rome,

know that this is your failing.

However much our base is stone

or mighty is your sailing,

the likes of you are not brought low

by sea wolves or by reivers --

Look to the glass to see your foe,

or check your head for fevers.

For one hand always slices through

the neck, however shielded.

It is your own. Its aim is true

with weapons you have wielded.

Or yet, the small, the scarce, unseen,

that sickens from inside,

encouraged by your deeds unclean

shall newer days elide.

Hail Rome! You shall die;

the world shall weep because of it,

the nations gnash their teeth and cry --

they shall not have enough of it

as highways built by human hands

are ripped to shreds by fragile grasses,

and trees break streets you have unmanned,

and stones block lonely passes,

or sealanes with no ghost or trace

forget you, love another;

and airlanes cease to know your trade,

but only wind that wuthers.

Black Squirrels

The black squirrels in Queen's Park

I miss; their scurry and their leap,

their eyes with cunning gleams

in heads half-cocked with listening,

their tails curled in the air:

I see them in my dreams.

Miryam

Little Jewish girl! You conquer all;

your ebon tress

that lightly falls

on homespun dress

more precious than a crown of gold,

your mouth that spoke sacred Shema's words

made sacredby your yes.

Your ear has heard

the heaven-song, your eye saw the sheen,

the shimmer of the things unseen.

Upon your Aramaic tongue

the world's own fate

at last had hung;

the angels wait

with bated spirit for your song,

from heaven's gateways spill and throng

to hear Israel in you speak:

They quest, they seek,

they headlong hurl

to wait upon a Jewish girl!

Saturday, September 24, 2011

The Sonnet's Scanty Plot of Ground

Nuns Fret Not at Their Convent's Narrow Room

by William Wordsworth

Nuns fret not at their convent's narrow room

And hermits are contented with their cells;

And students with their pensive citadels;

Maids at the wheel, the weaver at his loom,

Sit blithe and happy; bees that soar for bloom,

High as the highest Peak of Furness-fells,

Will murmur by the hour in foxglove bells:

In truth the prison, into which we doom

Ourselves, no prison is: and hence for me,

In sundry moods, 'twas pastime to be bound

Within the Sonnet's scanty plot of ground;

Pleased if some Souls (for such there needs must be)

Who have felt the weight of too much liberty,

Should find brief solace there, as I have found.

Friday, September 23, 2011

Dialogues, Part III

Robert Paul Wolff has been doing a series on Hume's Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion, and while it has been interesting, his post on Part III is an amusing example of how expectations blind one to the obvious evidence of the text. As always happens with Part III, Wolff is tripped up by the comment that Philo was confounded. Almost every flawed reading of the Dialogues trips up over this comment; no interpretation that fails to make genuine sense of it can possibly be right. And this becomes quite obvious when we look at the explanations that are usually given for it; one of the common ones being that which Wolff gives:

The absurdity of this interpretation is on its face: it makes the entire unity of the Dialogues consist in the stupidity of its characters, not just the stupidity of Demea (who admittedly is toyed with by Philo), but also the stupidity of Cleanthes (who is in fact treated throughout as an intelligent person) and the stupidity of Philo (who apparently never realizes that he can press these supposed advantages). The catastrophe of this interpretation, that it makes the work nothing more than a string of argumentative episodes strung together in poor literary fashion by nothing more than an unconvincing and implausible refusal on the part of its characters to recognize that they've been refuted conclusively, should in and of itself lead one to be suspicious of it. Wolff makes the comparison to Monty Python; but when we have a philosophical text that Hume obviously took seriously -- he put an immense amount of thought into it over several years, worked on it while he was dying, and did everything in his power to guarantee that it would be published after his death -- treated as something with no more coherence or rhyme and reason than a Monty Python skit, we should perhaps look again.

The fact of the matter is that Philo has not refuted Cleanthes's design argument, and Hume is well aware of it for four reasons. First, because he has a more sophisticated understanding of what is at stake in design arguments than people nowadays usually do; the design argument became so popular, and so widely regarded with respect, because it was closely tied up with philosophical accounts of science itself. In Hume's day this is very clear when you look at who was actually presenting design arguments, and they are the major scientific minds of Britain: Boyle, Newton, Newtonians like Colin Maclaurin, and the like. If you read the Dialogues closely, you notice that scientific inquiry comes up a lot, and there is a reason for it: the design argument is closely connected at the time with people's conceptions of what science does. Science discovers the laws of nature divine providence establishes throughout the world; the world is intelligible because there is an intellect that constructs it intelligibly. It's a common view in the period. And Hume cannot stop the argument before addressing it, because then it leaves up in the air whether and how the world has enough intelligibility to it to allow us to engage in scientific inquiry.

Second, Hume is not like some graduate student in analytic philosophy, amateurishly treating each argument as if it stood on its own, with a stand-alone refutation that has no implications for broader thought. Hume isn't looking for just any answer to the design argument; for very obvious reasons he wants one that is consistent with Humean principles, and does not have the implication that large parts of Hume's own worldview are wrong. And a close look at Philo's argument suggests that it is not consistent with things Hume has said elsewhere -- it presupposes an account of analogical inference that Hume does not actually accept, plausible as it may seem at first glance, and fails to take into account a feature of the design argument -- namely, its apparently intuitive plausibility -- which any moderate skeptic like Philo or Hume himself must take into account. In going for the kill, Philo, on Hume's own principles, has overstepped what he can actually commit himself to -- his 'refutation' of Cleanthes is, as Cleanthes quite rightly points out, inconsistent with his Humean defense of skepticism against Cleanthes's earlier arguments. I have talked about this before. It is also inconsistent with Hume's account of analogical inference in the Treatise.

Third, one of the major themes of the Dialogues is sociable friendship. While Demea is a bit of an interloper, Philo and Cleanthes are good friends; they remain so throughout the Dialogues, and much of Part XII is inexplicable unless we take this to be one of the important points of the work. Hume is not interested in attacking the design argument then calling it a day; he gave an early draft of the book (probably the first three parts) to a friend to make sure that he was portraying Cleanthes in the strongest light, and it is pretty clear that the book is supposed to convey the message that proponents and opponents of the design argument can get along amicably if they are moderate and rational about the subject. This message would not be served all that well if Cleanthes shows up, is roundly shown to be stupid, and the book ends.

And fourth, we have no reason whatsoever to think that Hume thought he ever had a solid refutation of the design argument, one that he himself could regard as solid, anyway. Indeed, in every text we have from Hume on the subject, throughout his entire life, he accepts that it tells us something about the world. Some of these comments are difficult to interpret, but it seems clear that his own view is that the argument works -- it just doesn't yield the very robust metaphysical and religious conclusions the Newtonians assume it does. This is in fact precisely what Philo himself will say in the Dialogues. Hume takes the argument far more seriously than Wolff does to begin with; as someone faced with Newtonian embrace of it, he has to do so, and more than that, he has to take it seriously because he believes that it makes a genuine point that must be taken seriously.

When we recognize that Philo's 'refutation' is not a refutation, and that Hume's recognition of this in Cleanthes's ability to confound Philo is not some arbitrary and senseless maneuver, the real brilliance of the Dialogues becomes clear: it is not a string of argumentative episodes linked implausibly by the stupidity and obstinacy of its characters; it is a crafted and unified text in which Philo and Cleanthes are both portrayed as bright people scoring genuine points off each other, and in which Hume takes the argument being considered as a serious matter with extensive ramifications both for philosophical Newtonianism (which Hume respects) and Humean skepticism itself, not as some set-piece that can be dispatched with a brief bit of undergraduate argument whose broader implications are never explored. The Dialogues don't end at Part III because Philo needs to try a new approach to the argument, which he does with a fair amount of success.

And it shows why Hume should be taken seriously as a philosopher. More than two hundred thirty years in the grave, and he still has a better grasp on the problem, and a more sophisticated approach to it, than academic philosophers usually do.

As the Emperor in Amadeus is wont to say, "Well, there it is." We have scarcely got through Part II of twelve parts, and both the Cosmological Argument and the Argument from Design are destroyed. What is Hume to do to keep his conversation afloat? His answer, to which he returns many times in the course of the Dialogues, is simply not to allow his characters to recognize that they have been defeated.

The absurdity of this interpretation is on its face: it makes the entire unity of the Dialogues consist in the stupidity of its characters, not just the stupidity of Demea (who admittedly is toyed with by Philo), but also the stupidity of Cleanthes (who is in fact treated throughout as an intelligent person) and the stupidity of Philo (who apparently never realizes that he can press these supposed advantages). The catastrophe of this interpretation, that it makes the work nothing more than a string of argumentative episodes strung together in poor literary fashion by nothing more than an unconvincing and implausible refusal on the part of its characters to recognize that they've been refuted conclusively, should in and of itself lead one to be suspicious of it. Wolff makes the comparison to Monty Python; but when we have a philosophical text that Hume obviously took seriously -- he put an immense amount of thought into it over several years, worked on it while he was dying, and did everything in his power to guarantee that it would be published after his death -- treated as something with no more coherence or rhyme and reason than a Monty Python skit, we should perhaps look again.

The fact of the matter is that Philo has not refuted Cleanthes's design argument, and Hume is well aware of it for four reasons. First, because he has a more sophisticated understanding of what is at stake in design arguments than people nowadays usually do; the design argument became so popular, and so widely regarded with respect, because it was closely tied up with philosophical accounts of science itself. In Hume's day this is very clear when you look at who was actually presenting design arguments, and they are the major scientific minds of Britain: Boyle, Newton, Newtonians like Colin Maclaurin, and the like. If you read the Dialogues closely, you notice that scientific inquiry comes up a lot, and there is a reason for it: the design argument is closely connected at the time with people's conceptions of what science does. Science discovers the laws of nature divine providence establishes throughout the world; the world is intelligible because there is an intellect that constructs it intelligibly. It's a common view in the period. And Hume cannot stop the argument before addressing it, because then it leaves up in the air whether and how the world has enough intelligibility to it to allow us to engage in scientific inquiry.

Second, Hume is not like some graduate student in analytic philosophy, amateurishly treating each argument as if it stood on its own, with a stand-alone refutation that has no implications for broader thought. Hume isn't looking for just any answer to the design argument; for very obvious reasons he wants one that is consistent with Humean principles, and does not have the implication that large parts of Hume's own worldview are wrong. And a close look at Philo's argument suggests that it is not consistent with things Hume has said elsewhere -- it presupposes an account of analogical inference that Hume does not actually accept, plausible as it may seem at first glance, and fails to take into account a feature of the design argument -- namely, its apparently intuitive plausibility -- which any moderate skeptic like Philo or Hume himself must take into account. In going for the kill, Philo, on Hume's own principles, has overstepped what he can actually commit himself to -- his 'refutation' of Cleanthes is, as Cleanthes quite rightly points out, inconsistent with his Humean defense of skepticism against Cleanthes's earlier arguments. I have talked about this before. It is also inconsistent with Hume's account of analogical inference in the Treatise.

Third, one of the major themes of the Dialogues is sociable friendship. While Demea is a bit of an interloper, Philo and Cleanthes are good friends; they remain so throughout the Dialogues, and much of Part XII is inexplicable unless we take this to be one of the important points of the work. Hume is not interested in attacking the design argument then calling it a day; he gave an early draft of the book (probably the first three parts) to a friend to make sure that he was portraying Cleanthes in the strongest light, and it is pretty clear that the book is supposed to convey the message that proponents and opponents of the design argument can get along amicably if they are moderate and rational about the subject. This message would not be served all that well if Cleanthes shows up, is roundly shown to be stupid, and the book ends.

And fourth, we have no reason whatsoever to think that Hume thought he ever had a solid refutation of the design argument, one that he himself could regard as solid, anyway. Indeed, in every text we have from Hume on the subject, throughout his entire life, he accepts that it tells us something about the world. Some of these comments are difficult to interpret, but it seems clear that his own view is that the argument works -- it just doesn't yield the very robust metaphysical and religious conclusions the Newtonians assume it does. This is in fact precisely what Philo himself will say in the Dialogues. Hume takes the argument far more seriously than Wolff does to begin with; as someone faced with Newtonian embrace of it, he has to do so, and more than that, he has to take it seriously because he believes that it makes a genuine point that must be taken seriously.

When we recognize that Philo's 'refutation' is not a refutation, and that Hume's recognition of this in Cleanthes's ability to confound Philo is not some arbitrary and senseless maneuver, the real brilliance of the Dialogues becomes clear: it is not a string of argumentative episodes linked implausibly by the stupidity and obstinacy of its characters; it is a crafted and unified text in which Philo and Cleanthes are both portrayed as bright people scoring genuine points off each other, and in which Hume takes the argument being considered as a serious matter with extensive ramifications both for philosophical Newtonianism (which Hume respects) and Humean skepticism itself, not as some set-piece that can be dispatched with a brief bit of undergraduate argument whose broader implications are never explored. The Dialogues don't end at Part III because Philo needs to try a new approach to the argument, which he does with a fair amount of success.

And it shows why Hume should be taken seriously as a philosopher. More than two hundred thirty years in the grave, and he still has a better grasp on the problem, and a more sophisticated approach to it, than academic philosophers usually do.

The Shape of Ancient Philosophy: V. The Roman Imperial Period

For what I am doing here, see this.

The political and military changes at the end of the Hellenistic period had a considerable effect on philosophy. Athens never recovered its former splendor, and philosophy ceased being as closely connected to central educational institutions as it had been. Philosophy's emphasis moves from schools like the Academy and the Lyceum and into the hands of local study groups and tutors scattered all over the Empire. This had an effect on both the way philosophy was done and the topics it covered: philosophers became much more interested in discovering what prior philosophers had thought. Doxography (the cataloging of the beliefs of different philosophical schools), biography, and commentary on philosophical classics became very important. Philosophers like Cicero (a student of Antiochus of Ascalon) were often interested less in developing their own views systematically and more in educating others as to the different philosophical views that had been held. Study of the natural world became less important in many places, while study of moral life moved to the forefront. The Stoics did very well in this environment; in fact, two of the most famous Stoic philosophers operate in this period: Epictetus and Marcus Aurelius. It perhaps says something about just how far Stoic ideas penetrated all classes of society that the former was a slave and the latter was an emperor.

Middle Platonism, however, arguably shapes much of the landscape of philosophy in the Roman Imperial period. I will simply note three of the most important here.

Eudorus of Alexandria: Eudorus put much of the focus of Middle Platonism on ethics. Eudorus's own conception of ethics was that the truly good life consists in becoming as like the gods as possible; he understood this to mean that the happy life consisted of intellectual contemplation of truth. He was also influenced by a number of Stoic ideas.

Plutarch of Chaeronea: Plutarch is easily the best known of all the Middle Platonists; this is in part due to a series of truly excellent philosophical and biographical essays that he wrote, almost all of which are well worth reading. He held that popular pagan religious views expressed philosophical truths in poetic and imaginative form, and attempt to unlock these truths by interpreting stories about the gods allegorically.

Philo of Alexandria: Also known as Philo Judaeus, Philo is the first significant Jewish philosopher of which we know much in Greek and Roman society. Alexandria, in Egypt, had a large and thriving Jewish population that had absorbed a considerable amount of Greek culture, and this included Greek philosophy. Philo and others set out to show the connections between Judaism and Greek philosophy, to interesting result. Philo held that God operated through the Logos, or divine Reason, which he associated with the figure of Wisdom in such Biblical passages as Proverbs 8:22.

The spread of philosophy among Hellenistic Jews would be important for the future of philosophy. The early Roman Imperial period also sees the rise of a new Jewish religion, Christianity, which caught on early in some Hellenistic Jewish populations around the Empire. Because of this even in the New Testament period Christians are adapting Middle Platonist language in order to express their religious views. The best example of this is the Gospel of John, where the word translated as 'Word' is the Greek word Logos:

It's unclear whether this use of the word Logos is due to Philo or (as is perhaps a bit more likely) a common Hellenistic Jewish background. Whatever the precise source, this adaptation of Middle Platonist language made it easier for later Middle Platonists, people like St. Justin Martyr and St. Clement of Alexandria, to combine their Christianity with their philosophical pursuits.

In the third century AD there is a palpable shift in the character and texture of Platonism, although it does not seem to have been noticed at the time. In the writings of people like Plotinus and Iamblichus we find a greater interest in being systematic and comprehensive: the very eclectic approach of Middle Platonism gives way to an attempt to think through all philosophical ideas with a very high degree of rigor. This new phase in philosophy is called Neoplatonism. To some extent one can see the last centuries of the Roman Imperial period as a struggle for dominance between Greek and Christian versions of Neoplatonism. With the dominance of Christianity over its pagan rivals, we begin to move out of what we usually call the Ancient period. It was a new world: the whole world, it seemed, would be Christian.

But history has a way of throwing surprises our way. Something new was brewing in Arabia. But we will get to that when we talk about philosophy in the Medieval period.

The political and military changes at the end of the Hellenistic period had a considerable effect on philosophy. Athens never recovered its former splendor, and philosophy ceased being as closely connected to central educational institutions as it had been. Philosophy's emphasis moves from schools like the Academy and the Lyceum and into the hands of local study groups and tutors scattered all over the Empire. This had an effect on both the way philosophy was done and the topics it covered: philosophers became much more interested in discovering what prior philosophers had thought. Doxography (the cataloging of the beliefs of different philosophical schools), biography, and commentary on philosophical classics became very important. Philosophers like Cicero (a student of Antiochus of Ascalon) were often interested less in developing their own views systematically and more in educating others as to the different philosophical views that had been held. Study of the natural world became less important in many places, while study of moral life moved to the forefront. The Stoics did very well in this environment; in fact, two of the most famous Stoic philosophers operate in this period: Epictetus and Marcus Aurelius. It perhaps says something about just how far Stoic ideas penetrated all classes of society that the former was a slave and the latter was an emperor.

Middle Platonism, however, arguably shapes much of the landscape of philosophy in the Roman Imperial period. I will simply note three of the most important here.

Eudorus of Alexandria: Eudorus put much of the focus of Middle Platonism on ethics. Eudorus's own conception of ethics was that the truly good life consists in becoming as like the gods as possible; he understood this to mean that the happy life consisted of intellectual contemplation of truth. He was also influenced by a number of Stoic ideas.

Plutarch of Chaeronea: Plutarch is easily the best known of all the Middle Platonists; this is in part due to a series of truly excellent philosophical and biographical essays that he wrote, almost all of which are well worth reading. He held that popular pagan religious views expressed philosophical truths in poetic and imaginative form, and attempt to unlock these truths by interpreting stories about the gods allegorically.

Philo of Alexandria: Also known as Philo Judaeus, Philo is the first significant Jewish philosopher of which we know much in Greek and Roman society. Alexandria, in Egypt, had a large and thriving Jewish population that had absorbed a considerable amount of Greek culture, and this included Greek philosophy. Philo and others set out to show the connections between Judaism and Greek philosophy, to interesting result. Philo held that God operated through the Logos, or divine Reason, which he associated with the figure of Wisdom in such Biblical passages as Proverbs 8:22.

The spread of philosophy among Hellenistic Jews would be important for the future of philosophy. The early Roman Imperial period also sees the rise of a new Jewish religion, Christianity, which caught on early in some Hellenistic Jewish populations around the Empire. Because of this even in the New Testament period Christians are adapting Middle Platonist language in order to express their religious views. The best example of this is the Gospel of John, where the word translated as 'Word' is the Greek word Logos:

In the beginning was the Word,

and the Word was with God,

and the Word was God.

He was with God in the beginning.

Through him all things were made;

without him nothing was made that has been made.

In him was life, and that life was the light of men.

The light shines in the darkness,

but the darkness has not understood it. (NIV)

and the Word was with God,

and the Word was God.

He was with God in the beginning.

Through him all things were made;

without him nothing was made that has been made.

In him was life, and that life was the light of men.

The light shines in the darkness,

but the darkness has not understood it. (NIV)

It's unclear whether this use of the word Logos is due to Philo or (as is perhaps a bit more likely) a common Hellenistic Jewish background. Whatever the precise source, this adaptation of Middle Platonist language made it easier for later Middle Platonists, people like St. Justin Martyr and St. Clement of Alexandria, to combine their Christianity with their philosophical pursuits.

In the third century AD there is a palpable shift in the character and texture of Platonism, although it does not seem to have been noticed at the time. In the writings of people like Plotinus and Iamblichus we find a greater interest in being systematic and comprehensive: the very eclectic approach of Middle Platonism gives way to an attempt to think through all philosophical ideas with a very high degree of rigor. This new phase in philosophy is called Neoplatonism. To some extent one can see the last centuries of the Roman Imperial period as a struggle for dominance between Greek and Christian versions of Neoplatonism. With the dominance of Christianity over its pagan rivals, we begin to move out of what we usually call the Ancient period. It was a new world: the whole world, it seemed, would be Christian.

But history has a way of throwing surprises our way. Something new was brewing in Arabia. But we will get to that when we talk about philosophy in the Medieval period.

Music on My Mind

Al Stewart, "Katherine of Oregon". Stewart is an excellent lyricist; this one, in part because it's simultaneously both very simple and very clever in its lyrical technique, is easily his most charming.

Thursday, September 22, 2011

The Shape of Ancient Philosophy: IV. Hellenistic Philosophy

For what I am doing here, see this.

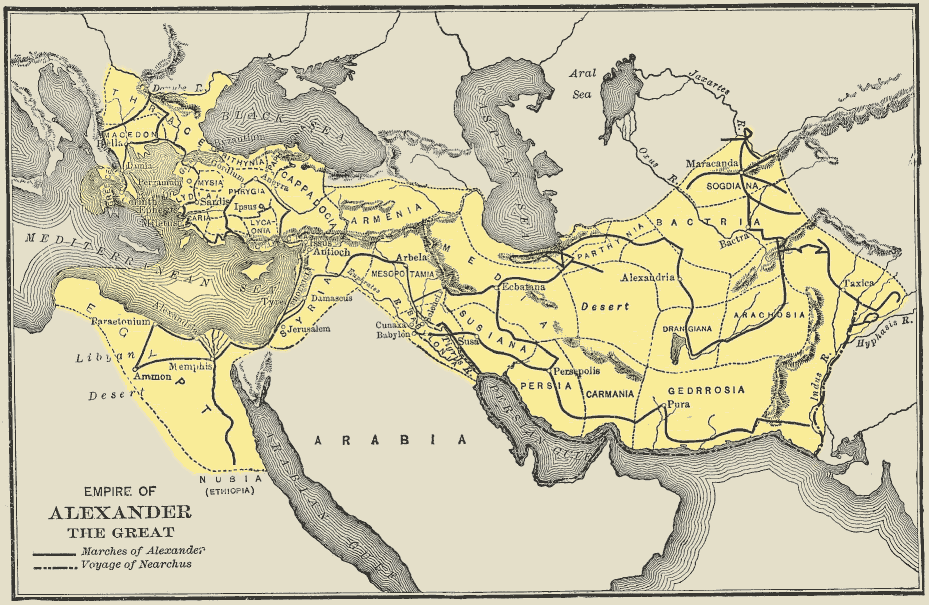

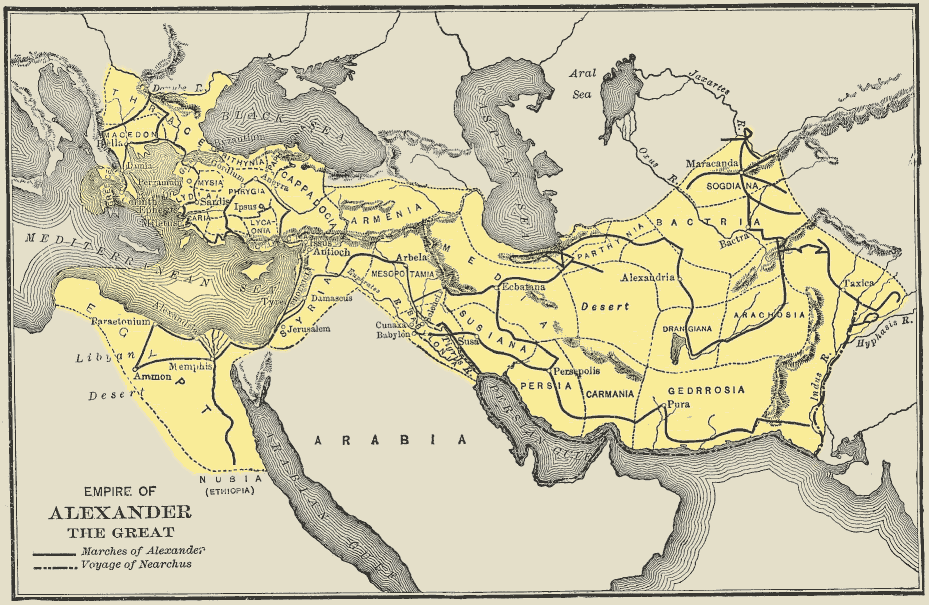

The Hellenistic period is a period consisting of the dominance of Greek culture, from roughly the time that Alexander the Great established his empire to roughly the time that the rising power of the Roman Republic becomes an Empire itself. As an arbitrary date, we can say it begins with the death of Alexander in India in 323 BC and ends somewhere between 146 BC, when Rome conquers the Greek homeland, and 30 BC, when Rome conquers the last major fragment of Alexander's empire, the Ptolemaic Kingdom of Egypt ruled by Cleopatra. From the philosophical perspective the period is dominated by schools, which begin as local institutions for education and gradually become major philosophical movements. Many schools had been founded by Socrates' students, but most of them did not last long; from that first generation only Plato's Academy survives. It is joined by three others, and these four schools of thought are what people usually mean when they speak of Hellenistic philosophy.

The New Academics: The purpose of Plato's Academy had never been simply to spread Plato's own ideas. It was instead a place for people interested in intellectual pursuits to come together and exchange ideas. Because of this, Plato's successors in the Academy often took it in new directions. The Platonic origin remained important, and the Academy preserved Plato's dialogues, but Plato's successors did not feel bound to follow him slavishly. The primary tone of the Academy in the Hellenistic period was set by Arcesilaus, who became the sixth head of the Academy somewhere in the middle of the third century BC. We don't have a precise idea of his views; he doesn't seem to have written anything, and descriptions of his teaching are somewhat confused. We do know that he advocated some form of skepticism; according to Cicero, he held that he knew nothing, not even whether he knew nothing, but if he did say that, it's not clear that it was meant to be taken completely literally. Whatever his precise views were, the Academy in this period becomes associated with a moderate skepticism -- the claim that we cannot know that things are true, but, at most, we can have reason to think them truth-like. Because this is a shift from the early days of the Academy, this phase of the history of the school is often called 'the New Academy', although this label is often reserved for the phase of the Academy that begins with the tenth head of the school, Carneades, who may be responsible for the moderateness of Academic skepticism; when this distinction is made, the phase begun by Arcesilaus is called 'the Second Academy' or 'the Middle Academy'.

The Peripatetics: The Peripatetic school was founded by Aristotle; they met at the Lyceum in Athens. The word 'peripatetic' means 'walking around'; apparently Aristotle liked to teach while walking. The Lyceum had a rockier history than the Academy; Aristotle's works were nearly lost several times, and, indeed, we are almost certainly missing a significant portion of his writings. One of Aristotle's major interests had been the natural world, and the Peripatetics of the Hellenistic period seem to have focused largely on this topic. A number of significant mathematicians and historians were associated with the school in one way or another.

The Stoics: Stoicism was founded by Zeno of Citium, and became one of the most thriving philosophical movements of the Hellenistic period. Called Stoics because they taught at the Stoa Poikile (which means 'The Painted Porch'), the Stoics aimed to become sages, completely wise individuals ruled wholly by reason and therefore always capable of rising above their passions, thinking with tranquil calm regardless of what happened to them. They argued vehemently against the Academics that it was possible to know things with certainty, and they argued vehemently against the Epicureans that pleasure was not the greatest good. They held that the universe was a living being -- God, in fact, and that divine Reason or logos pervaded everything. Our own reason is a sort of participation in this divine reason. Since they held that Nature is God, and thus full of divine Reason, they often describe the good life as living according to Nature or living according to Reason. Because of their interest in reason, the Stoics made a number of advances in logic; however, we only have fragments of their work in this field.

The Epicureans: Epicurus of Samos argued that the good life consisted in a life of tranquil pleasures. Good and evil are explained in terms of pleasure and pain. The Epicureans were also materialists: they held that everything consisted of atomoi, indivisible particles, moving in a void. They were the most anti-Socratic of the Hellenistic schools, but Epicurus may have been influenced by the school of Aristippus, one of Socrates' students; Aristippus also held that the good life consists in pleasure, although he seems to have allowed a wider range of acceptable pleasures than Epicurus. He certainly was influenced by the thought of Democritus, an earlier philosopher who had also proposed an atomic theory of the universe. Because Epicurus' students in Athens met in his garden, the Epicurean school was often called The Garden. Interestingly, the Epicureans were the most static school of the Hellenistic period: their doctrines changed very little over their entire history. Part of this seems to be because students in The Garden were required to swear an oath to uphold Epicurus' basic teachings. A good description of Epicurean doctrine is found in Epicurus' Letter to Menoeceus.

In addition to these four major schools, there were two other significant philosophical movements; both of them were less organized than the above schools.

The Cynics: The first full Cynic is usually said to be Diogenes of Sinope. He seems to have been heavily influenced by Antisthenes, one of Socrates' students, and to have argued that happiness consists in living according to nature, which they understood as complete self-sufficiency, free of all social convention and the cares that come from having material possessions. The name 'Cynic' literally means 'dog-like' in Greek; we don't know for certain why they were called this. Some say that it was because Antisthenes taught at the Cynosarges gymnasium; but it may have been an insult (that they lived like dogs), which they began to wear with pride. Zeno of Citium was almost certainly heavily influenced by Cynic views.

There are many anecdotes and legends about Diogenes of Sinope, who was once called "Socrates gone mad". In statues and paintings he is usually depicted holding a lantern; this stems from the most famous of these anecdotes, in which Diogenes goes around in broad daylight with a lit lantern, looking into various corners of the city. When asked what he is doing, he replies with something along the lines of, "I am looking for an honest man; I still have not found one."

The Skeptics: One of the philosophers who travelled with Alexander the Great was Pyrrho of Elis. We don't know precisely what his views were, but it is said that he advocated complete suspension of judgment: dogmatic belief was a source of misery, because human beings cannot know anything, so happiness was to be found by merely going with the appearances and not being dogmatic about anything. This inspired a philosophical movement in the late Hellenistic period, under a philosopher named Aenesidemus, which was called Pyrrhonism. We don't have a clear history of how the later movement was related to Pyrrho himself. It seems plausible, however, that in between the two there were scattered skeptics not associated with the particular version of skepticism found in the New Academy.

The actual physical institution of the Academy seems to have been destroyed due to war in 86 BC (as was the Lyceum), although teaching went on elsewhere. About this time Antiochus of Ascalon broke away from the skepticism of the New Academy in order to revive the teaching of the Academy under Plato: what he founded is sometimes called the Old Academy because of this. What he actually started was a philosophical movement that came to be called Middle Platonism; it is this movement that will come to dominate the early Roman Imperial period.

For times were changing. The Academy and the Lyceum had been ravaged in the First Mithridatic War, a failed rebellion of Greek cities against Rome's ever-increasing power. And after the death of Cleopatra VII of Egypt in 30 BC, Rome ruled the Mediterranean Sea with complete sway.

The Hellenistic period is a period consisting of the dominance of Greek culture, from roughly the time that Alexander the Great established his empire to roughly the time that the rising power of the Roman Republic becomes an Empire itself. As an arbitrary date, we can say it begins with the death of Alexander in India in 323 BC and ends somewhere between 146 BC, when Rome conquers the Greek homeland, and 30 BC, when Rome conquers the last major fragment of Alexander's empire, the Ptolemaic Kingdom of Egypt ruled by Cleopatra. From the philosophical perspective the period is dominated by schools, which begin as local institutions for education and gradually become major philosophical movements. Many schools had been founded by Socrates' students, but most of them did not last long; from that first generation only Plato's Academy survives. It is joined by three others, and these four schools of thought are what people usually mean when they speak of Hellenistic philosophy.

The New Academics: The purpose of Plato's Academy had never been simply to spread Plato's own ideas. It was instead a place for people interested in intellectual pursuits to come together and exchange ideas. Because of this, Plato's successors in the Academy often took it in new directions. The Platonic origin remained important, and the Academy preserved Plato's dialogues, but Plato's successors did not feel bound to follow him slavishly. The primary tone of the Academy in the Hellenistic period was set by Arcesilaus, who became the sixth head of the Academy somewhere in the middle of the third century BC. We don't have a precise idea of his views; he doesn't seem to have written anything, and descriptions of his teaching are somewhat confused. We do know that he advocated some form of skepticism; according to Cicero, he held that he knew nothing, not even whether he knew nothing, but if he did say that, it's not clear that it was meant to be taken completely literally. Whatever his precise views were, the Academy in this period becomes associated with a moderate skepticism -- the claim that we cannot know that things are true, but, at most, we can have reason to think them truth-like. Because this is a shift from the early days of the Academy, this phase of the history of the school is often called 'the New Academy', although this label is often reserved for the phase of the Academy that begins with the tenth head of the school, Carneades, who may be responsible for the moderateness of Academic skepticism; when this distinction is made, the phase begun by Arcesilaus is called 'the Second Academy' or 'the Middle Academy'.

The Peripatetics: The Peripatetic school was founded by Aristotle; they met at the Lyceum in Athens. The word 'peripatetic' means 'walking around'; apparently Aristotle liked to teach while walking. The Lyceum had a rockier history than the Academy; Aristotle's works were nearly lost several times, and, indeed, we are almost certainly missing a significant portion of his writings. One of Aristotle's major interests had been the natural world, and the Peripatetics of the Hellenistic period seem to have focused largely on this topic. A number of significant mathematicians and historians were associated with the school in one way or another.

The Stoics: Stoicism was founded by Zeno of Citium, and became one of the most thriving philosophical movements of the Hellenistic period. Called Stoics because they taught at the Stoa Poikile (which means 'The Painted Porch'), the Stoics aimed to become sages, completely wise individuals ruled wholly by reason and therefore always capable of rising above their passions, thinking with tranquil calm regardless of what happened to them. They argued vehemently against the Academics that it was possible to know things with certainty, and they argued vehemently against the Epicureans that pleasure was not the greatest good. They held that the universe was a living being -- God, in fact, and that divine Reason or logos pervaded everything. Our own reason is a sort of participation in this divine reason. Since they held that Nature is God, and thus full of divine Reason, they often describe the good life as living according to Nature or living according to Reason. Because of their interest in reason, the Stoics made a number of advances in logic; however, we only have fragments of their work in this field.

The Epicureans: Epicurus of Samos argued that the good life consisted in a life of tranquil pleasures. Good and evil are explained in terms of pleasure and pain. The Epicureans were also materialists: they held that everything consisted of atomoi, indivisible particles, moving in a void. They were the most anti-Socratic of the Hellenistic schools, but Epicurus may have been influenced by the school of Aristippus, one of Socrates' students; Aristippus also held that the good life consists in pleasure, although he seems to have allowed a wider range of acceptable pleasures than Epicurus. He certainly was influenced by the thought of Democritus, an earlier philosopher who had also proposed an atomic theory of the universe. Because Epicurus' students in Athens met in his garden, the Epicurean school was often called The Garden. Interestingly, the Epicureans were the most static school of the Hellenistic period: their doctrines changed very little over their entire history. Part of this seems to be because students in The Garden were required to swear an oath to uphold Epicurus' basic teachings. A good description of Epicurean doctrine is found in Epicurus' Letter to Menoeceus.

In addition to these four major schools, there were two other significant philosophical movements; both of them were less organized than the above schools.

The Cynics: The first full Cynic is usually said to be Diogenes of Sinope. He seems to have been heavily influenced by Antisthenes, one of Socrates' students, and to have argued that happiness consists in living according to nature, which they understood as complete self-sufficiency, free of all social convention and the cares that come from having material possessions. The name 'Cynic' literally means 'dog-like' in Greek; we don't know for certain why they were called this. Some say that it was because Antisthenes taught at the Cynosarges gymnasium; but it may have been an insult (that they lived like dogs), which they began to wear with pride. Zeno of Citium was almost certainly heavily influenced by Cynic views.

There are many anecdotes and legends about Diogenes of Sinope, who was once called "Socrates gone mad". In statues and paintings he is usually depicted holding a lantern; this stems from the most famous of these anecdotes, in which Diogenes goes around in broad daylight with a lit lantern, looking into various corners of the city. When asked what he is doing, he replies with something along the lines of, "I am looking for an honest man; I still have not found one."

The Skeptics: One of the philosophers who travelled with Alexander the Great was Pyrrho of Elis. We don't know precisely what his views were, but it is said that he advocated complete suspension of judgment: dogmatic belief was a source of misery, because human beings cannot know anything, so happiness was to be found by merely going with the appearances and not being dogmatic about anything. This inspired a philosophical movement in the late Hellenistic period, under a philosopher named Aenesidemus, which was called Pyrrhonism. We don't have a clear history of how the later movement was related to Pyrrho himself. It seems plausible, however, that in between the two there were scattered skeptics not associated with the particular version of skepticism found in the New Academy.

The actual physical institution of the Academy seems to have been destroyed due to war in 86 BC (as was the Lyceum), although teaching went on elsewhere. About this time Antiochus of Ascalon broke away from the skepticism of the New Academy in order to revive the teaching of the Academy under Plato: what he founded is sometimes called the Old Academy because of this. What he actually started was a philosophical movement that came to be called Middle Platonism; it is this movement that will come to dominate the early Roman Imperial period.

For times were changing. The Academy and the Lyceum had been ravaged in the First Mithridatic War, a failed rebellion of Greek cities against Rome's ever-increasing power. And after the death of Cleopatra VII of Egypt in 30 BC, Rome ruled the Mediterranean Sea with complete sway.

Wednesday, September 21, 2011

The Shape of Ancient Philosophy: III. Sophists and Socratics

For what I am doing here, see this.

In the fifth century, Athens began to enter a golden age of prosperity and strength, and the inevitable happened: people started coming to Athens. New ways of thinking that had developed at the edge of the Greek world began to come together here, interacting with both each other and traditional Athenian ideas. The mixture was sometimes rather volatile. When the Ionian philosopher Anaxagoras came to Athens, he was accused of impiety (apparently for saying that the sun was not a god but a burning rock) and had to flee the city.

Into this mix stepped the Sophists. The original Sophists were all from outside of Athens -- Protagoras and Prodicus were from Ionia, Gorgias from Sicily. They came proposing to teach Athenian youths everything they needed to know in order to become successful in the thriving democratic society of Athens. Putting their achievement in the most positive light, we can say that they were serious proponents of democracy; they taught anyone, regardless of background, as long as they paid. They were also educational innovators. Prior to the Sophists students were educated by sunousia, that is, by just being hanging around with adults as the adults did their work, until they, too, had picked up the skills. The Sophists recognized that this was inefficient, and so began to develop artificial education: classrooms, lectures, and the like. These things cost more money than the sunousia method, but the major Sophists were all very good at what they did: teaching the things you needed to know to become powerfully persuasive in the assemblies of Athens. So people paid.

There were reactions. Some people thought the Sophists were just stirring up trouble; they were occasionally banned from cities. But the most important reaction for philosophical purposes took a different direction entirely. This reaction was spearheaded by Socrates. Socrates held that there were fundamental flaws in the Sophists' approach to education. Knowledge was not a list of formulas, not a set of tips and tricks; it was not something that could be bought or sold, nor could it be put into a student's mind by a teacher. The role of a teacher on Socrates' view was to play midwife: the student's mind, pregnant with truth, must bring it forth itself; the teacher does not give the student the truth any more than the midwife gives the mother the baby, but instead helps to make it easier for the mother to do the hard work of brining a new child into the world. Likewise, in education the student does all the discovery: the teacher just helps make the discovery happen more smoothly. Moreover, everyone benefits from the student's discovery, so Socrates did not believe in charging fees for teaching.

Socrates died in 399 BC. His students, however, spread out all over the Greek world, founding schools, usually on Socratic principles. There were many such schools founded, but one outshines them all: Plato's. Plato founded his school at the Grove of Akademos; because of that, it became known as the Academy. There are two reasons why Plato is the most important of all of Socrates's students:

(1) The Academy outlasted all other schools founded by the students of Socrates. It had an excellent location, was organized in a way that made it very flexible, and became the preeminent example of a philosophical institution.

(2) Plato was an extraordinarily good writer, and his philosophical dialogues are true masterpieces of Greek literature and thought. Other students had written Socratic dialogues, but we only have fragments of them; except for some dialogues by Xenophon that have also survived, Plato's dialogues are the only ones that survive in full.

Plato had many students, but the most famous is Aristotle. Unlike Plato and Socrates, he was not Athenian; he was Macedonian, in fact. At one point he even tutored the son of the king of Macedonia. The son of the king of Macedonia was named Alexander, and he went on to conquer much of the known world. Because of this he was called Alexander the Great.

With Alexander the Great, however, we enter the Hellenistic period of philosophy.

In the fifth century, Athens began to enter a golden age of prosperity and strength, and the inevitable happened: people started coming to Athens. New ways of thinking that had developed at the edge of the Greek world began to come together here, interacting with both each other and traditional Athenian ideas. The mixture was sometimes rather volatile. When the Ionian philosopher Anaxagoras came to Athens, he was accused of impiety (apparently for saying that the sun was not a god but a burning rock) and had to flee the city.

Into this mix stepped the Sophists. The original Sophists were all from outside of Athens -- Protagoras and Prodicus were from Ionia, Gorgias from Sicily. They came proposing to teach Athenian youths everything they needed to know in order to become successful in the thriving democratic society of Athens. Putting their achievement in the most positive light, we can say that they were serious proponents of democracy; they taught anyone, regardless of background, as long as they paid. They were also educational innovators. Prior to the Sophists students were educated by sunousia, that is, by just being hanging around with adults as the adults did their work, until they, too, had picked up the skills. The Sophists recognized that this was inefficient, and so began to develop artificial education: classrooms, lectures, and the like. These things cost more money than the sunousia method, but the major Sophists were all very good at what they did: teaching the things you needed to know to become powerfully persuasive in the assemblies of Athens. So people paid.

There were reactions. Some people thought the Sophists were just stirring up trouble; they were occasionally banned from cities. But the most important reaction for philosophical purposes took a different direction entirely. This reaction was spearheaded by Socrates. Socrates held that there were fundamental flaws in the Sophists' approach to education. Knowledge was not a list of formulas, not a set of tips and tricks; it was not something that could be bought or sold, nor could it be put into a student's mind by a teacher. The role of a teacher on Socrates' view was to play midwife: the student's mind, pregnant with truth, must bring it forth itself; the teacher does not give the student the truth any more than the midwife gives the mother the baby, but instead helps to make it easier for the mother to do the hard work of brining a new child into the world. Likewise, in education the student does all the discovery: the teacher just helps make the discovery happen more smoothly. Moreover, everyone benefits from the student's discovery, so Socrates did not believe in charging fees for teaching.

Socrates died in 399 BC. His students, however, spread out all over the Greek world, founding schools, usually on Socratic principles. There were many such schools founded, but one outshines them all: Plato's. Plato founded his school at the Grove of Akademos; because of that, it became known as the Academy. There are two reasons why Plato is the most important of all of Socrates's students:

(1) The Academy outlasted all other schools founded by the students of Socrates. It had an excellent location, was organized in a way that made it very flexible, and became the preeminent example of a philosophical institution.

(2) Plato was an extraordinarily good writer, and his philosophical dialogues are true masterpieces of Greek literature and thought. Other students had written Socratic dialogues, but we only have fragments of them; except for some dialogues by Xenophon that have also survived, Plato's dialogues are the only ones that survive in full.

Plato had many students, but the most famous is Aristotle. Unlike Plato and Socrates, he was not Athenian; he was Macedonian, in fact. At one point he even tutored the son of the king of Macedonia. The son of the king of Macedonia was named Alexander, and he went on to conquer much of the known world. Because of this he was called Alexander the Great.

With Alexander the Great, however, we enter the Hellenistic period of philosophy.

Tuesday, September 20, 2011

Sweet Rhyme and Pure Reason

"You may not see it now," said the Princess of Pure Reason, looking knowingly at Milo's puzzled face, "but whatever we learn has a purpose and whatever we do affects everything and everyone else, if even in the tiniest way. Why, when a housefly flaps his wings, a breeze goes round the world; when a speck of dust falls to the ground, the entire planet weighs a little more; and when you stamp your foot, the earth moves slightly off its course. Whenever you laugh, gladness spreads like the ripples in a pond; and whenever you're sad, no one anywhere can be really happy. And it's much the same thing with knowledge, for whenever you learn something new, the whole world becomes that much richer."

"And remember, also," added the Princess of Sweet Rhyme, "that many places you would like to see are just off the map and many things you want to know are just out of sight or a little beyond your reach. But someday you'll reach them all, for what you learn today, for no reason at all, will help you discover all the wonderful secrets of tomorrow."

Apparently we just passed the fiftieth anniversary of the publication of one of the great children's classics of the 20th century: Norton Juster's The Phantom Tollbooth, which ever since has taught children that Rhyme and Reason settle every problem, that it's not enough to learn if you do not learn why you learn anything at all, and that the only thing worse than wasting time is killing it. So perhaps it's time to set out again with the trusty watchdog Tock and the fussy and blustering Humbug, and hear again the Which, Faintly Macabre, tell the story of the princesses of the Kingdom of Wisdom.

The Shape of Ancient Philosophy: II. The Eleatic Challenge

For what I am doing here, see this.

It was not only in Ionia that serious and systematic thinking could be found. On the other side of the Greek world, in Elea, a Greek colony in Southern Italy, Parmenides began to think through the implications of change. Out of his conclusions grew what has come to be known as the Eleatic School. There were several major thinkers in this philosophical movement.

Parmenides: We have only one fragmentary poem from Parmenides, but it gives us some idea of what his philosophical views may have been. In the poem Parmenides has a vision of a goddess who tells him to distinguish the Way of Knowledge from the Way of Opinion. The Way of Knowledge concerns what exists, and what truly exists does not change. Reality (as we would call it) is immutable, complete, indivisible, and eternal. What exists cannot come from anything other than itself, because the only thing that is not what exists is what does not exist (nothing); and nothing comes from nothing. What exists cannot be known by sensory perception, but only by logos, reason: sensory perception only gives us what seems to exist, and what seems to exist is different from what exists. What seems to exist is mere appearance; it is not real.

The notable thing about this is that Parmenides has taken the discussion of change that we found in the Ionian philosophers and raised it to an entirely new level: we are not merely talking about changing things, but about existence itself. Also important is the fact that he raises as a serious and important issue the distinction between knowledge and opinion and tries to draw a precise line between the two. Both of these points will be very influential on later philosophers. The argument that what exists cannot change was particularly important for the later course of Greek philosophy; it is often called the Eleatic Challenge: how can what exists come from what does not exist, which seems to be what happens in every change?

Zeno of Elea: The most famous of Parmenides' followers is Zeno of Elea. In Parmenides (at least what survives of his work) we have a poetic expression of the Eleatic Challenge. Zeno took that Challenge and put it in rigorous analytical forms. Because of this Aristotle calls him the inventor of dialectic, the process of analyzing claims through careful use of arguments and counter-arguments. Some of these arguments are justly famous; although they come to very paradoxical conclusions, they are well designed and thought-provoking, and through their profound simplicity have stood the test of time.

Melissus of Samos: Like Zeno, Melissus took Parmenidean ideas and formulated arguments for them. One of his positions was that the universe is infinite in time and space; he also (according to Plutarch) claimed that we should not say anything about the gods because we do not know anything about them. The arguments attributed to him seem creative, and Melissus seems to have been influential in making people aware of Eleatic ideas, but the reception of his work does not seem to have been completely laudatory: Aristotle says that his thought was crude and his arguments were absurd, and clearly regards him as inferior to Parmenides and Zeno. It's difficult for us to say because we only have fragments of Melissus's work surviving in quotations found in other people's works.

The Eleatic Challenge plays an important role in the history of philosophy because it directs our attention to the problem of change. Any serious attempt to understand the world must come to grips with the question, "What is change?" It is a question that is not as easy to answer as it might at first seem. The emphasis Zeno and Melissus place on careful rational argument is of immense importance, too. With them we have gone beyond the Ionian attempt to find natural explanations; they show the value of trying to explain things in rational and well-argued ways.

It was not only in Ionia that serious and systematic thinking could be found. On the other side of the Greek world, in Elea, a Greek colony in Southern Italy, Parmenides began to think through the implications of change. Out of his conclusions grew what has come to be known as the Eleatic School. There were several major thinkers in this philosophical movement.

Parmenides: We have only one fragmentary poem from Parmenides, but it gives us some idea of what his philosophical views may have been. In the poem Parmenides has a vision of a goddess who tells him to distinguish the Way of Knowledge from the Way of Opinion. The Way of Knowledge concerns what exists, and what truly exists does not change. Reality (as we would call it) is immutable, complete, indivisible, and eternal. What exists cannot come from anything other than itself, because the only thing that is not what exists is what does not exist (nothing); and nothing comes from nothing. What exists cannot be known by sensory perception, but only by logos, reason: sensory perception only gives us what seems to exist, and what seems to exist is different from what exists. What seems to exist is mere appearance; it is not real.

The notable thing about this is that Parmenides has taken the discussion of change that we found in the Ionian philosophers and raised it to an entirely new level: we are not merely talking about changing things, but about existence itself. Also important is the fact that he raises as a serious and important issue the distinction between knowledge and opinion and tries to draw a precise line between the two. Both of these points will be very influential on later philosophers. The argument that what exists cannot change was particularly important for the later course of Greek philosophy; it is often called the Eleatic Challenge: how can what exists come from what does not exist, which seems to be what happens in every change?

Zeno of Elea: The most famous of Parmenides' followers is Zeno of Elea. In Parmenides (at least what survives of his work) we have a poetic expression of the Eleatic Challenge. Zeno took that Challenge and put it in rigorous analytical forms. Because of this Aristotle calls him the inventor of dialectic, the process of analyzing claims through careful use of arguments and counter-arguments. Some of these arguments are justly famous; although they come to very paradoxical conclusions, they are well designed and thought-provoking, and through their profound simplicity have stood the test of time.

Melissus of Samos: Like Zeno, Melissus took Parmenidean ideas and formulated arguments for them. One of his positions was that the universe is infinite in time and space; he also (according to Plutarch) claimed that we should not say anything about the gods because we do not know anything about them. The arguments attributed to him seem creative, and Melissus seems to have been influential in making people aware of Eleatic ideas, but the reception of his work does not seem to have been completely laudatory: Aristotle says that his thought was crude and his arguments were absurd, and clearly regards him as inferior to Parmenides and Zeno. It's difficult for us to say because we only have fragments of Melissus's work surviving in quotations found in other people's works.

The Eleatic Challenge plays an important role in the history of philosophy because it directs our attention to the problem of change. Any serious attempt to understand the world must come to grips with the question, "What is change?" It is a question that is not as easy to answer as it might at first seem. The emphasis Zeno and Melissus place on careful rational argument is of immense importance, too. With them we have gone beyond the Ionian attempt to find natural explanations; they show the value of trying to explain things in rational and well-argued ways.

Monday, September 19, 2011

The Shape of Ancient Philosophy: I. The Ionian Enchantment

For what I am doing here, see this.

In some sense philosophy is essential to any civilization: civilizations have to order priorities, and setting things in order is what philosophical thinking is. However, this is often very unsystematic. We can trace philosophy in a more systematic sense, at least in the Western world, back to ancient Ionia. Ionia was a Greek colony in what is modern-day Turkey.

One of the major cities of ancient Ionia was Miletus, which was a seacoast city near the mouth of the Maeander River. In the sixth century BC Miletus was the center of of a burst of creative activity which formed what has since become known (somewhat misleadingly, because it was not a unified movement) as the Milesian school of pre-Socratic philosophy. Three thinkers in particular are important to this movement:

Thales: If one were to try to identify a 'first philosopher' among the ancient Greeks, Thales would be a good choice; Aristotle, in fact, will later call him exactly this. We don't know many precise details about him (or any of the Milesians) but we do know that he was interested in the natural world and accurately predicted the eclipse of May 28, 585 BC. He became famous for his wisdom and understanding of the world. We have no writings from him, but according to Aristotle Thales was the first to try to explain things not by appealing to the gods but by trying to figure out the nature of the world. According to Thales, the nature of the world was water. Given that Thales came from wet Miletus, one can see how someone might think this: water can be gas, liquid, or solid, so it's only a short distance to thinking that perhaps all other changes in the world are variations on the same process water undergoes.

Anaximander: Anaximander took up the same questions Thales (who seems to have been his teacher) did. A late work by Themistius claims that he was the first philosopher to write a treatise on nature, but this might be a mistake. He is said to have suggested that the actual nature that Thales had been looking for was not water but what he called the apeiron, or unbounded: something so indeterminate that it can be opposite things like water and fire, air and earth. He may have been the first to suggest that the earth was suspended in the middle of the world, not resting on anything else, and may also have been the first to realize that the Sun was a very large object; he also seems to have held that thunder was not an action of the gods but simply the clouds hitting each other.

Anaximenes: Anaximenes seems to have held the view that Thales's underlying substance was air. We don't know much else about him, but he does seem to have tried to go farther than others had in analyzing the classical list of the four elements (fire, water, earth, and air) by identifying them in terms of more fundamental features (cold and hot, wet and dry).

Milesian ideas seem to have been taken up and debated elsewhere in Ionia, and there are a number of names of non-Milesians from Ionia that come down to us. The most notable of these was

Heraclitus: A notable thinker from Ephesus, he seems to have held that the root substance was fire. But he went farther than the Milesians by recognizing that the fundamental issue was not so much the basic material as the nature of change itself. According to fragmentary sayings attributed to him, he held that everything is constantly changing ('You cannot step into the same river twice') and that change is a conflict of opposites. By raising the question of change itself, Heraclitus is essentially taking the Milesian project and raising it to a more abstract level.

All of the Ionian philosophers are notable for trying to go beyond pious explanation of events by appeal to the gods in order to determine what it is in the nature of things that makes things change the way they do. Because of this, one sometimes hears the phrase "Ionian Enchantment" associated with discussions of natural science: the Ionian Enchantment is the wonder generated by thinking of the natural world as intelligible and orderly, and is sometimes said to be the heart of the scientific approach to the world. We have to be careful of anachronism, but if we interpret the idea that the world has an intelligible order following natural laws broadly enough, it isn't unreasonable to say that it begins with the new questions that were raised by the Ionians. Of course, things had a long way to go; but the mere fact of raising these questions about change was an innovation, and the beginning of a long and fruitful journey.

In some sense philosophy is essential to any civilization: civilizations have to order priorities, and setting things in order is what philosophical thinking is. However, this is often very unsystematic. We can trace philosophy in a more systematic sense, at least in the Western world, back to ancient Ionia. Ionia was a Greek colony in what is modern-day Turkey.

One of the major cities of ancient Ionia was Miletus, which was a seacoast city near the mouth of the Maeander River. In the sixth century BC Miletus was the center of of a burst of creative activity which formed what has since become known (somewhat misleadingly, because it was not a unified movement) as the Milesian school of pre-Socratic philosophy. Three thinkers in particular are important to this movement:

Thales: If one were to try to identify a 'first philosopher' among the ancient Greeks, Thales would be a good choice; Aristotle, in fact, will later call him exactly this. We don't know many precise details about him (or any of the Milesians) but we do know that he was interested in the natural world and accurately predicted the eclipse of May 28, 585 BC. He became famous for his wisdom and understanding of the world. We have no writings from him, but according to Aristotle Thales was the first to try to explain things not by appealing to the gods but by trying to figure out the nature of the world. According to Thales, the nature of the world was water. Given that Thales came from wet Miletus, one can see how someone might think this: water can be gas, liquid, or solid, so it's only a short distance to thinking that perhaps all other changes in the world are variations on the same process water undergoes.

Anaximander: Anaximander took up the same questions Thales (who seems to have been his teacher) did. A late work by Themistius claims that he was the first philosopher to write a treatise on nature, but this might be a mistake. He is said to have suggested that the actual nature that Thales had been looking for was not water but what he called the apeiron, or unbounded: something so indeterminate that it can be opposite things like water and fire, air and earth. He may have been the first to suggest that the earth was suspended in the middle of the world, not resting on anything else, and may also have been the first to realize that the Sun was a very large object; he also seems to have held that thunder was not an action of the gods but simply the clouds hitting each other.

Anaximenes: Anaximenes seems to have held the view that Thales's underlying substance was air. We don't know much else about him, but he does seem to have tried to go farther than others had in analyzing the classical list of the four elements (fire, water, earth, and air) by identifying them in terms of more fundamental features (cold and hot, wet and dry).

Milesian ideas seem to have been taken up and debated elsewhere in Ionia, and there are a number of names of non-Milesians from Ionia that come down to us. The most notable of these was

Heraclitus: A notable thinker from Ephesus, he seems to have held that the root substance was fire. But he went farther than the Milesians by recognizing that the fundamental issue was not so much the basic material as the nature of change itself. According to fragmentary sayings attributed to him, he held that everything is constantly changing ('You cannot step into the same river twice') and that change is a conflict of opposites. By raising the question of change itself, Heraclitus is essentially taking the Milesian project and raising it to a more abstract level.

All of the Ionian philosophers are notable for trying to go beyond pious explanation of events by appeal to the gods in order to determine what it is in the nature of things that makes things change the way they do. Because of this, one sometimes hears the phrase "Ionian Enchantment" associated with discussions of natural science: the Ionian Enchantment is the wonder generated by thinking of the natural world as intelligible and orderly, and is sometimes said to be the heart of the scientific approach to the world. We have to be careful of anachronism, but if we interpret the idea that the world has an intelligible order following natural laws broadly enough, it isn't unreasonable to say that it begins with the new questions that were raised by the Ionians. Of course, things had a long way to go; but the mere fact of raising these questions about change was an innovation, and the beginning of a long and fruitful journey.

The Shape of Ancient Philosophy, Prologue

One of the kinds of courses I teach is a hybrid course, half online, half on campus; in order to manage this while keeping the course competitive, a great deal needs to be offloaded to some kind of online segment. One of the ways I have for doing this is by constructing learning modules on the background, which the students do independently, thus freeing up time for closer look at specifics in our actual class meetings. Since I am slowly reviewing some of what I have, I thought I would put up a sample model and get any thoughts or comments from readers. It's worth keeping in mind that by its nature it is (1) introductory and therefore somewhat imprecise and approximate, although I hope not inaccurate; and (2) preparatory to actual classes, i.e., not completely stand-alone). I'll unreel it here in segments over the next few days.

Sunday, September 18, 2011

Then I Shall Take Out This Afternoon

September, 1918

by Amy Lowell

This afternoon was the colour of water falling through sunlight;

The trees glittered with the tumbling of leaves;

The sidewalks shone like alleys of dropped maple leaves,

And the houses ran along them laughing out of square, open windows.

Under a tree in the park,

Two little boys, lying flat on their faces,

Were carefully gathering red berries

To put in a pasteboard box.

Some day there will be no war,

Then I shall take out this afternoon

And turn it in my fingers,

And remark the sweet taste of it upon my palate,

And note the crisp variety of its flights of leaves.

To-day I can only gather it

And put it into my lunch-box,

For I have time for nothing

But the endeavour to balance myself

Upon a broken world.