In the Gloaming

by Meta Orred

In the gloaming, O my darling ! when the lights are dim and low,

And the quiet shadows falling softly come and softly go,

And the winds are sobbing faintly with a gentle unknown woe,

Will you think of me and love me as you once did, long ago?

In the gloaming, O my darling ! when the merry song is stilled,

And your voices sink to whispers, and the thought your heart has thrilled

All day long ’neath jest and laughter, rises, and your eyes are filled

With bitter tears for my lost face—think only of a trust fulfilled.

In the gloaming, O my darling! think not bitterly of me,

Though I passed away in silence, left you lonely, set you free ;

For my heart was crushed with longing—what had been could never be :

It was best to leave you quickly—best for you, and best for me.

Saturday, June 16, 2018

Scottish Poetry XVI

Friday, June 15, 2018

Dashed Off XIII

review accountability vs imputation accountability vs recourse accountability

Narnian Christmas is Dickensian: benevolent Yule, relief from winter.

The elements of accountability are authority, review, recourse. (Is there anything else to add?)

If a society becomes free, it increases the kinds of privileges available, because privileges are what free people leverage in political matters. A free society has many kinds of privilege that operate in many kinds of ways, and that are available for many. (Note, however, that the particular privilege as such is not the freedom that leverages it.)

the articles of the Creed as conditions for learning the faith

The divine facts of revelation are things God has made in His people.

'resemblance is not a relation' // 'correlation is not causation'

sentimentalist accounts of obligation (presumably in the form of quasi-compulsive feelings)

sentimentalist consequentialist: classical utilitarianism

rationalist consequentialist: ideal utilitarianism?

sentimentalist deontology: ?

rationalist deontology: Kant, etc.

sentimentalist virtue ethics: Hume

rationalist virtue ethics: Aristotle

positivist vs naturalist accounts of authenticity

natural law, its layers

(1) as legislated by reason

(2) as legislated by God

(3) as confirmed by divine positive legislation

HoP as philosophy (rational contemplation so as to find the true) interacting with philology (human making so as to get the certain)

the principle of totality & treating more important things as more important

Journalistic reporting is inherently anecdotal; even statistics are treated as anecdotal evidence.

the Beatitudes as "a sort of veiled interior biography of Jesus" (Ratzinger)

intelligere:

(1) perfecte legere

(2) aperte cognoscere

Vico: the human mind is intrinsically such that extra se habet omnia

Vico's primary weakness on scientia is an insufficient appreciation of constitutive causes.

Dedekind's 'free creation' and mathematics as a liberal art

Is there a relation between the paradox of compassoin and the paradox of tragedy?

Confucian ethics would be excellently suited for government ethics, for obvious historical reasons.

due process as a particular form of rites

'always or for the most part' universals : y'all :: strict universals : all y'all

certum as image of verum

Beginning with models we make, we rise to truths about what is modeled by causation, remotion, and eminence.

We often think of hierarchy as rising upward, but it can just as easily be thought of as moving inward.

sacrament as gift through symbol

traditionary argument as linguistic Kalam argument

Bodily integrity as such is expressed through but must be distinguished from physical, emotional, and behavioral protections for it.

Bodily integrity is an active self-protection, not a passive system of boundaries.

bodily integrity as the material person himself/herself

A protest can only be just to the extent that it is integrated with a larger project of working for common good.

Many of the state-like features of the Catholic Church were not borrowed from the state but by the state as the latter expanded its power.

A religious community has the right to look after its physical health as part of its spiritual health.

Intersectionality is like trying to model circles with polygons.

Shallow sympathy is not justice.

commonwealth: "association of a multitude of rational beings united by common agreement on the objects of their love" (Augustine)

Just government must be promissory and regular; that is, it must involve keeping promises and acting by rules.

Everything that happens is, in terms of its relation, ordered narratively by the human mind.

To place myself in my imagination requires situating myself such that something is outside of me.

traditionary argument vs exemplary theory of language (an extrinsic/intrinsic divide)

Consensus gentium is concerned with a sort of endoxic Box.

locomotion: unde, qua, quo

reserve in communicating religious knowledge as the natural expression of the principle of remotion

- note that reserve here can't be conflated with silence

A universal church has room for cozy spaces; but it is not itself a cozy space.

chronic vigor as showing a sort of self-motion (life as a note of the Church)

Newman Letter to the Bishop of Oxford, notes of the Church of England: life possession, freedom from party-titles, ancient descent, unbroken continuance, agreement in doctrine with ancient church

"Those of Bellarmine's Notes, which she certainly has not, are intercommunion with Christendom, the glory of miracles, and the prophetical light...."

The mind that will not bow down before truth cannot be trusted to uphold truth.

Literally nobody's political beliefs are held to strict Cliffordian standards by anybody.

In addition to the intrinsic characters of the Notes of the Church, there are notes of the Notes. For instance, saint-making is part of the Note of Sanctity; memorial and vernation of the saints is a note of that Note. The true Church would make saints whether anyone knew or cared; but their knowing and caring manifests that it does, diagnostically.

The Notes of the Church as such can be recognized by hearts of good will and thoughtful regard, requiring no elaborate education or abstruse reasoning; but some of the notes of the Notes, i.e., the signs indicating the primary signs, may involve precisely these things. Why, then, are they ever necessary? Precisely because prejudice, or confusion, or the like, may require an indirect route to what others can find directly; or, in otherwords as a concession to weakness, for some need precisely these complex things, given their circumstances, to grasp the simple things.

Narnian Christmas is Dickensian: benevolent Yule, relief from winter.

The elements of accountability are authority, review, recourse. (Is there anything else to add?)

If a society becomes free, it increases the kinds of privileges available, because privileges are what free people leverage in political matters. A free society has many kinds of privilege that operate in many kinds of ways, and that are available for many. (Note, however, that the particular privilege as such is not the freedom that leverages it.)

the articles of the Creed as conditions for learning the faith

The divine facts of revelation are things God has made in His people.

'resemblance is not a relation' // 'correlation is not causation'

sentimentalist accounts of obligation (presumably in the form of quasi-compulsive feelings)

sentimentalist consequentialist: classical utilitarianism

rationalist consequentialist: ideal utilitarianism?

sentimentalist deontology: ?

rationalist deontology: Kant, etc.

sentimentalist virtue ethics: Hume

rationalist virtue ethics: Aristotle

positivist vs naturalist accounts of authenticity

natural law, its layers

(1) as legislated by reason

(2) as legislated by God

(3) as confirmed by divine positive legislation

HoP as philosophy (rational contemplation so as to find the true) interacting with philology (human making so as to get the certain)

the principle of totality & treating more important things as more important

Journalistic reporting is inherently anecdotal; even statistics are treated as anecdotal evidence.

the Beatitudes as "a sort of veiled interior biography of Jesus" (Ratzinger)

intelligere:

(1) perfecte legere

(2) aperte cognoscere

Vico: the human mind is intrinsically such that extra se habet omnia

Vico's primary weakness on scientia is an insufficient appreciation of constitutive causes.

Dedekind's 'free creation' and mathematics as a liberal art

Is there a relation between the paradox of compassoin and the paradox of tragedy?

Confucian ethics would be excellently suited for government ethics, for obvious historical reasons.

due process as a particular form of rites

'always or for the most part' universals : y'all :: strict universals : all y'all

certum as image of verum

Beginning with models we make, we rise to truths about what is modeled by causation, remotion, and eminence.

We often think of hierarchy as rising upward, but it can just as easily be thought of as moving inward.

sacrament as gift through symbol

traditionary argument as linguistic Kalam argument

Bodily integrity as such is expressed through but must be distinguished from physical, emotional, and behavioral protections for it.

Bodily integrity is an active self-protection, not a passive system of boundaries.

bodily integrity as the material person himself/herself

A protest can only be just to the extent that it is integrated with a larger project of working for common good.

Many of the state-like features of the Catholic Church were not borrowed from the state but by the state as the latter expanded its power.

A religious community has the right to look after its physical health as part of its spiritual health.

Intersectionality is like trying to model circles with polygons.

Shallow sympathy is not justice.

commonwealth: "association of a multitude of rational beings united by common agreement on the objects of their love" (Augustine)

Just government must be promissory and regular; that is, it must involve keeping promises and acting by rules.

Everything that happens is, in terms of its relation, ordered narratively by the human mind.

To place myself in my imagination requires situating myself such that something is outside of me.

traditionary argument vs exemplary theory of language (an extrinsic/intrinsic divide)

Consensus gentium is concerned with a sort of endoxic Box.

locomotion: unde, qua, quo

reserve in communicating religious knowledge as the natural expression of the principle of remotion

- note that reserve here can't be conflated with silence

A universal church has room for cozy spaces; but it is not itself a cozy space.

chronic vigor as showing a sort of self-motion (life as a note of the Church)

Newman Letter to the Bishop of Oxford, notes of the Church of England: life possession, freedom from party-titles, ancient descent, unbroken continuance, agreement in doctrine with ancient church

"Those of Bellarmine's Notes, which she certainly has not, are intercommunion with Christendom, the glory of miracles, and the prophetical light...."

The mind that will not bow down before truth cannot be trusted to uphold truth.

Literally nobody's political beliefs are held to strict Cliffordian standards by anybody.

In addition to the intrinsic characters of the Notes of the Church, there are notes of the Notes. For instance, saint-making is part of the Note of Sanctity; memorial and vernation of the saints is a note of that Note. The true Church would make saints whether anyone knew or cared; but their knowing and caring manifests that it does, diagnostically.

The Notes of the Church as such can be recognized by hearts of good will and thoughtful regard, requiring no elaborate education or abstruse reasoning; but some of the notes of the Notes, i.e., the signs indicating the primary signs, may involve precisely these things. Why, then, are they ever necessary? Precisely because prejudice, or confusion, or the like, may require an indirect route to what others can find directly; or, in otherwords as a concession to weakness, for some need precisely these complex things, given their circumstances, to grasp the simple things.

Scottish Poetry XV

Paraphrase of the First Psalm

by Robert Burns

The man, in life wherever plac'd,

Hath happiness in store,

Who walks not in the wicked's way,

Nor learns their guilty lore!

Nor from the seat of scornful pride

Casts forth his eyes abroad,

But with humility and awe

Still walks before his God.

That man shall flourish like the trees,

Which by the streamlets grow;

The fruitful top is spread on high,

And firm the root below.

But he whose blossom buds in guilt

Shall to the ground be cast,

And, like the rootless stubble, tost

Before the sweeping blast.

For why? that God the good adore,

Hath giv'n them peace and rest,

But hath decreed that wicked men

Shall ne'er be truly blest.

Thursday, June 14, 2018

Evening Note for Thursday, June 14

Thought for the Evening: The Notion of Militia in Scottish Enlightenment Thought

Militias of one sort or another have been a longstanding tradition, but they became a major political topic in the Florentine Renaissance, which put forward two basic ideas: standing armies are inherently dangerous to liberty, and the primary right and responsibility for the defense of any people is the people themselves, qua militia. This spread out across Europe, and interacted with the British common law, which recognized that the whole body of men could be called up as a defensive authority, either against lawbreakers (in posse comitatus) or against invaders (in militia). The British Empire found the militia to be increasingly useful in the colonies as a supplement to regular military forces (particularly the American colonies -- the militia in Bermuda turned out to be particularly successful). And in 1757, Parliament passed the Militia Act to put the English militia on a more organized and regular footing. Scotland, however, was left out in the cold for much of this: a similar bill for Scotland was defeated in 1760. The Parliament of Great Britain was primarily English, and the English did not trust the Scots. Regular regiments had been formed, but a more expansive involvement of the Scots in their own defense was inconsistent with the British policy on dealing with Scottish uprisings, of which there were, of course, quite a few in the eighteenth century, due to the Jacobites. That policy was heavily focused on disarmament of the Highlands. This frustrated Scots, even and perhaps especially pro-Union Scots, because (1) it was yet another way in which the Scots were treated by the English as a second-class member of Great Britain; (2) the actual practical effect of such disarmament attempts had largely been to leave disarmed Union-sympathizing Scots in the Highlands at the mercy of armed Jacobites; and (3) it essentially meant that the Scots had limited power and authority over their own defense, so that habits of dependency would inevitably develop.

Even before the Union there had been some reflection on the importance of the militia to Scottish life, and this helped to set up for much of the Scottish disatisfaction at the failure of the Union Parliament to recognize a Scottish militia. The key figure in this tradition is Andrew Fletcher of Saltoun, who in 1698 wrote an influential work, A Discourse of Government With Relation to Militias. In this work he develops an extended argument for the superiority of a militia over standing army. It makes the argument that it is absolutely essential to a free people for their state not to have a monopoly on force; those who are dependent on standing armies inevitably are at the mercy of those who control the armies. Since the general argument against this view is that standing armies are necessary for defense against other standing armies, he spends some time arguing against this. First, the danger of a standing army is so great that it is more serious than that of foreign invasion. But, second, Fletcher argues that one can distinguish between an "ordinary and ill-regulated" militia and a "well-regulated" militia, the latter being one that is actively supported and given the means to have some organization and training.

Fletcher's conclusions take quite a strong form, then -- the militia is one of the differences between a free people and unfree people:

In the course of making this argument, he will make a number of other arguments that will also have some influence on later discussions. First, that arms "are the only true badges of liberty". Second, that the disparagement of militias tends to have what we might call it a classist motivation. In a regime with a weak militia, the wealthy and powerful can get out of out their responsibilities to protect the common good; in practice, the poor end up fighting and dying for the liberty of the rich. Third, that militia service, even very basic militia service, can serve an educational purpose in cultivating free and courageous habits of mind, as people see themselves as contributing to their own defense.

It is perhaps unsurprising, then, that when the Scottish Militia Bill was defeated, Scottish intellectuals began to consider what could be done to advocate for a Scottish militia. The result of this, given the club culture of Edinburgh intellectuals, was the Militia Club, founded in 1762. It would very soon afterwards change its name to the Poker Club -- the name was less confrontational and conveyed the notion of stirring up support the way a poker stirs up a fire. Much of the cream of Edinburgh literate society, including David Hume and Adam Smith, were members.

Of the members, perhaps the greatest driving force was Adam Ferguson. He had served as a chaplain in the British army and was a strong admirer of military virtues. Heavily influenced by the civic republican tradition that had been revived by Florentine humanists, he regarded the diffusing of the power of defense among the people as part of the progress of society, and in 1756 had written a work on the subject, Reflections Previous to the Establishment of a Militia. One of Ferguson's arguments is that the foundation of a militia has to begin at a much more fundamental point than actually getting people together for exercises: a militia depends crucially on people already being ready to bear arms, and this requires that they already be accustomed to them. Thus Ferguson argues that "every Restraint should be taken away by which the People are hindered from having or amusing themselves with Arms." This is indeed one of the advantages of a thriving militia over a standing army; the latter tends to predominate in terms of order and discipline, but the former can bring a "Love of Arms" that no amount of military training can instill. Besides "a general Use of arms among the People", Ferguson also argues that ranks in the militia should have an honor equal to other forms of honor (like titles of nobility) and given special precedence in certain matters, in order to increase the interest in active participation by a love of honor. This double foundation, general use of arms and pursuit of honor, Ferguson regards as the one form of defense that is not itself a danger to the liberty of the people.

Fletcher and Ferguson do not agree on all things (for instance, Fletcher opposes, and Ferguson supports, the king having direct authority over the militia), and neither of them agree on all things with others in the Scottish Enlightenment who touch on the matter. For instance, Adam Smith, although agreeing with them about some of the benefits, has comments that can plausibly be taken as suggesting that he has much less of a problem with standing armies than they do.

The notion of a militia had its banner success in 1776, when American militias served as the first basis for what would become the Continental Army. The Scots would get their legally recognized militia in 1797, in part because so many regular troops had been siphoned off to handle the French and the Americans. Pressure from the Napoleonic Wars kept the militia alive as both a form of home defense and a reserve. However, Ferguson had remarked on the tendency of trade empires to depreciate militias in favor of standing armies, and this seems to have held generally throughout the world, as militias residuated into a kind of reserve power and then into a mere nominal existence. The civic-republican interest in the notion that a free people are a militia faded almost everywhere, and the World Wars led to Britain's own militias largely being assimilated by the standing army. Despite its once being regarded as a pillar of freedom, it is hardly recognized today; the Swiss still have the militia culture that once so impressed Scottish and American liberals, and fragments of the idea still play a major role in the national discourse of the United States, but you would be hard pressed to find much of substance anywhere else.

Various Links of Interest

* Richard Marshall interviews Malcolm Keating on Indian philosophy of language.

* Rogier Creemers, China's Social Credit System: An Evolving Practice of Control (PDF)

* One of the most famous and influential psychology experiments of all time, the Stanford Prison Experiment, was, it turns out, manipulated by the experimenter to get the conclusion it reached.

* Trump threw the media in a frenzy (as he does) earlier in June over the question of whether he could pardon himself. In fact, it is a legally unclear area and has been disputed for some time; the two main reference points being the lack of constitutional restriction (except for impeachment) and the fact that legal pardons usually cannot be for the person issuing them. Jack Goldsmith has an evenhanded summary of the current lay of the dispute: A Smorgasbord of Views on Self-Pardoning (PDF).

Currently Reading

Gordon MacKay Brown, Magnus

Neil Gaiman, Norse Mythology

John C. Wright, Superluminary: The Space Vampires

Militias of one sort or another have been a longstanding tradition, but they became a major political topic in the Florentine Renaissance, which put forward two basic ideas: standing armies are inherently dangerous to liberty, and the primary right and responsibility for the defense of any people is the people themselves, qua militia. This spread out across Europe, and interacted with the British common law, which recognized that the whole body of men could be called up as a defensive authority, either against lawbreakers (in posse comitatus) or against invaders (in militia). The British Empire found the militia to be increasingly useful in the colonies as a supplement to regular military forces (particularly the American colonies -- the militia in Bermuda turned out to be particularly successful). And in 1757, Parliament passed the Militia Act to put the English militia on a more organized and regular footing. Scotland, however, was left out in the cold for much of this: a similar bill for Scotland was defeated in 1760. The Parliament of Great Britain was primarily English, and the English did not trust the Scots. Regular regiments had been formed, but a more expansive involvement of the Scots in their own defense was inconsistent with the British policy on dealing with Scottish uprisings, of which there were, of course, quite a few in the eighteenth century, due to the Jacobites. That policy was heavily focused on disarmament of the Highlands. This frustrated Scots, even and perhaps especially pro-Union Scots, because (1) it was yet another way in which the Scots were treated by the English as a second-class member of Great Britain; (2) the actual practical effect of such disarmament attempts had largely been to leave disarmed Union-sympathizing Scots in the Highlands at the mercy of armed Jacobites; and (3) it essentially meant that the Scots had limited power and authority over their own defense, so that habits of dependency would inevitably develop.

Even before the Union there had been some reflection on the importance of the militia to Scottish life, and this helped to set up for much of the Scottish disatisfaction at the failure of the Union Parliament to recognize a Scottish militia. The key figure in this tradition is Andrew Fletcher of Saltoun, who in 1698 wrote an influential work, A Discourse of Government With Relation to Militias. In this work he develops an extended argument for the superiority of a militia over standing army. It makes the argument that it is absolutely essential to a free people for their state not to have a monopoly on force; those who are dependent on standing armies inevitably are at the mercy of those who control the armies. Since the general argument against this view is that standing armies are necessary for defense against other standing armies, he spends some time arguing against this. First, the danger of a standing army is so great that it is more serious than that of foreign invasion. But, second, Fletcher argues that one can distinguish between an "ordinary and ill-regulated" militia and a "well-regulated" militia, the latter being one that is actively supported and given the means to have some organization and training.

Fletcher's conclusions take quite a strong form, then -- the militia is one of the differences between a free people and unfree people:

A good militia is of such importance to a nation, that it is the chief part of the constitution of any free government. For though as to other things, the constitution be never so slight, a good militia will always preserve the public liberty. But in the best constitution that ever was, as to all other parts of government, if the militia be not upon a right foot, the liberty of that people must perish. The militia of ancient Rome, the best that ever was in any government, made her mistress of the world: but standing armies enslaved that great people, and their excellent militia and freedom perished together. The Lacedemonians continued eight hundred years free, and in great honour, because they had a good militia. The Swisses at this day are the freest, happiest, and the people of all Europe who can best defend themselves, because they have the best militia.

In the course of making this argument, he will make a number of other arguments that will also have some influence on later discussions. First, that arms "are the only true badges of liberty". Second, that the disparagement of militias tends to have what we might call it a classist motivation. In a regime with a weak militia, the wealthy and powerful can get out of out their responsibilities to protect the common good; in practice, the poor end up fighting and dying for the liberty of the rich. Third, that militia service, even very basic militia service, can serve an educational purpose in cultivating free and courageous habits of mind, as people see themselves as contributing to their own defense.

It is perhaps unsurprising, then, that when the Scottish Militia Bill was defeated, Scottish intellectuals began to consider what could be done to advocate for a Scottish militia. The result of this, given the club culture of Edinburgh intellectuals, was the Militia Club, founded in 1762. It would very soon afterwards change its name to the Poker Club -- the name was less confrontational and conveyed the notion of stirring up support the way a poker stirs up a fire. Much of the cream of Edinburgh literate society, including David Hume and Adam Smith, were members.

Of the members, perhaps the greatest driving force was Adam Ferguson. He had served as a chaplain in the British army and was a strong admirer of military virtues. Heavily influenced by the civic republican tradition that had been revived by Florentine humanists, he regarded the diffusing of the power of defense among the people as part of the progress of society, and in 1756 had written a work on the subject, Reflections Previous to the Establishment of a Militia. One of Ferguson's arguments is that the foundation of a militia has to begin at a much more fundamental point than actually getting people together for exercises: a militia depends crucially on people already being ready to bear arms, and this requires that they already be accustomed to them. Thus Ferguson argues that "every Restraint should be taken away by which the People are hindered from having or amusing themselves with Arms." This is indeed one of the advantages of a thriving militia over a standing army; the latter tends to predominate in terms of order and discipline, but the former can bring a "Love of Arms" that no amount of military training can instill. Besides "a general Use of arms among the People", Ferguson also argues that ranks in the militia should have an honor equal to other forms of honor (like titles of nobility) and given special precedence in certain matters, in order to increase the interest in active participation by a love of honor. This double foundation, general use of arms and pursuit of honor, Ferguson regards as the one form of defense that is not itself a danger to the liberty of the people.

Fletcher and Ferguson do not agree on all things (for instance, Fletcher opposes, and Ferguson supports, the king having direct authority over the militia), and neither of them agree on all things with others in the Scottish Enlightenment who touch on the matter. For instance, Adam Smith, although agreeing with them about some of the benefits, has comments that can plausibly be taken as suggesting that he has much less of a problem with standing armies than they do.

The notion of a militia had its banner success in 1776, when American militias served as the first basis for what would become the Continental Army. The Scots would get their legally recognized militia in 1797, in part because so many regular troops had been siphoned off to handle the French and the Americans. Pressure from the Napoleonic Wars kept the militia alive as both a form of home defense and a reserve. However, Ferguson had remarked on the tendency of trade empires to depreciate militias in favor of standing armies, and this seems to have held generally throughout the world, as militias residuated into a kind of reserve power and then into a mere nominal existence. The civic-republican interest in the notion that a free people are a militia faded almost everywhere, and the World Wars led to Britain's own militias largely being assimilated by the standing army. Despite its once being regarded as a pillar of freedom, it is hardly recognized today; the Swiss still have the militia culture that once so impressed Scottish and American liberals, and fragments of the idea still play a major role in the national discourse of the United States, but you would be hard pressed to find much of substance anywhere else.

Various Links of Interest

* Richard Marshall interviews Malcolm Keating on Indian philosophy of language.

* Rogier Creemers, China's Social Credit System: An Evolving Practice of Control (PDF)

* One of the most famous and influential psychology experiments of all time, the Stanford Prison Experiment, was, it turns out, manipulated by the experimenter to get the conclusion it reached.

* Trump threw the media in a frenzy (as he does) earlier in June over the question of whether he could pardon himself. In fact, it is a legally unclear area and has been disputed for some time; the two main reference points being the lack of constitutional restriction (except for impeachment) and the fact that legal pardons usually cannot be for the person issuing them. Jack Goldsmith has an evenhanded summary of the current lay of the dispute: A Smorgasbord of Views on Self-Pardoning (PDF).

Currently Reading

Gordon MacKay Brown, Magnus

Neil Gaiman, Norse Mythology

John C. Wright, Superluminary: The Space Vampires

Scottish Poetry XIV

There Grew in Bonnie Scotland

by Robert Allan

There grew in bonnie Scotland

A thistle and a brier,

And aye they twined and clasped,

Like sisters kind and dear:

The rose it was sae bonnie,

It could ilk bosom charm;

The thistle spread its thorny leaves

To keep the rose frae harm.

A bonnie laddie tended

The rose baith air an' late;

He watered it, and fanned it,

And wove it with his fate;

And the leal hearts of Scotland

Prayed it might never fa',

The thistle was sae bonnie green,

The rose sae like the snaw.

But the weird sisters sat

Where Hope's fair emblems grew;

They drapt a drap upon the rose

O' bitter, blasting dew;

And aye they twined the mystic thread,

But ere their task was done,

The snaw-white shade it disappeared—

It withered in the sunl

A bonnie laddie tended

The rose baith air an' late;

He watered it, and fanned it,

And wove it with his fate; . . .

But the thistle tap it withered,—

Winds bore it far awa,

And Scotland's heart was broken

For the rose sae like the snaw!

Wednesday, June 13, 2018

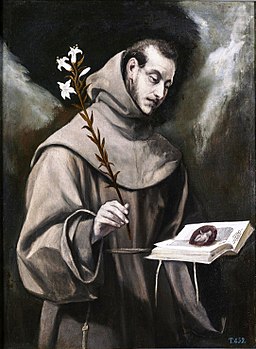

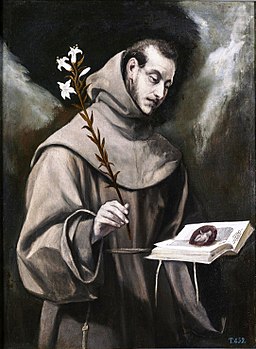

Doctor Evangelicus

Today was the feast of St. Anthony of Padua, Doctor of the Church. He was born Fernando Martins de Bulhões in Lisbon in about 1195. He eventually joined the Franciscans and was discovered to have an extraordinary gift for preaching on Scripture, for which reason he is occasional called the Ark of the Testament. He died of ergotism on June 13, 1231, which is why the disease is sometimes called St. Anthony's Fire, and was canonized in May of the next year. The Alamo was originally named after him, Misión San Antonio de Valero, which is why the city of San Antonio has the name it does.

Scottish Poetry XIII

Expectans Expectavi

by Charles Sorley

From morn to midnight, all day through,

I laugh and play as others do,

I sin and chatter, just the same

As others with a different name.

And all year long upon the stage

I dance and tumble and do rage

So vehemently, I scarcely see

The inner and eternal me.

I have a temple I do not

Visit, a heart I have forgot,

A self that I have never met,

A secret shrine—and yet, and yet

This sanctuary of my soul

Unwitting I keep white and whole,

Unlatched and lit, if Thou should'st care

To enter or to tarry there.

With parted lips and outstretched hands

And listening ears Thy servant stands,

Call Thou early, call Thou late,

To Thy great service dedicate.

May 1915

Tuesday, June 12, 2018

Scottish Poetry XII

Cuddle Doon

by Alexander Anderson

"The bairnies cuddle doon at nicht,

Wi' muckle faucht an' din;

O, try and sleep, ye waukrife rogues,

Your faither's comin' in.

They never heed a word I speak;

I try to gie a froon,

But aye I hap them up, an' cry,

"O, bairnies, cuddle doon."

Wee Jamie wi' the curly heid—

He aye sleeps next the wa',

Bangs up an' cries, "I want a piece"—

The rascal starts them a'.

I rin an' and fetch them pieces, drinks,

They stop awee the soun',

Then draw the blankets up an' cry,

"Noo, weanies, cuddle doon."

But ere five minutes gang, wee Rab

Cries oot, frae 'neath the claes,

"Mither, mak' Tam gie ower at ance,

He's kittlin' wi' his taes."

The mischiefs in that Tam for tricks,

He'd bother half the toon;

But aye I hap them up an' cry,

"O, bairnies, cuddle doon."

At length they hear their faither's fit,

An', as he steeks the door,

They turn their faces to the wa',

While Tam pretends to snore.

"Hae a' the weans been gude?" he asks,

As he pits aff his shoon.

"The bairnies, John, are in their beds,

An' lang since cuddled doon."

An' just afore we bed oorsel's,

We look at oor wee lambs;

Tam has his airm roun' wee Rab's neck,

An' Rab his airm roun' Tam's.

I lift wee Jamie up the bed,

An' as I straik each croon,

I whisper, till my heart fills up,

"O, bairnies, cuddle doon."

The bairnies cuddle doon at nicht

Wi' mirth that's dear to me;

But sune the big warl's cark an' care

Will quaten doon their glee.

Yet, come what will to ilka ane,

May He who sits aboon

Aye whisper, though their pows be bauld,

"O, bairnies, cuddle doon."

Monday, June 11, 2018

Voyages Extraordinaire #32: Deux ans de vacances

During the night of March 9, 1860, the clouds, merging with the sea, limited the view to a few fathoms. On this disintegrated sea, over which the waves broke beneath a livid gleam, a fragile vessel was driven, almost bare of sail. It was a hundred-ton yacht - a schooner - the name of schooners in England and America. This schooner was called the Sloughi, although in vain would one have sought to read this name on her back-board, which an accident -- a stroke of the sea or a collision -- had partly torn from below the crest.

(My translation.) By a freak accident, a group of boys, aged eight to thirteen, are alone on a boat in the middle of a raging storm that results in their landing, weeks later, on a deserted island, lost and on their own. Under the leadership of the big boys -- the resourceful Briant, the intelligent but haughty Doniphan, and the personable and diplomatic Gordon -- with the help of the younger cabin boy, Moko, they survive, as the title says, for two years, under dangerous conditions, for the adventure, and the vacation, of a lifetime.

Deux ans de vacances, often titled in English, Adrift in the Pacific, is a good opportunity to discuss briefly the problems with Verne translations. Early translators often translated with a rather free hand, in the belief that they were making a more exciting story; names were changed, passages abridged or cut, and, occasionally, passages added. The choices made in such translations were occasionally harmless -- nobody is really put out by the change of Verne's 'Cyrus Smith' in The Mysterious Island to 'Cyrus Harding'. Even in such cases something can be lost -- Verne chose names for characters very carefully -- but this is a minor thing, and one can imagine any number of cases in which it would be justifiable. Indeed, some cases -- like quoting the actual Ossian instead of Verne's French paraphrases in The Green Ray, could very well enrich the story. But this is not the general course of things, and the result is often shoddy work, with changes that cannot seriously be justified in terms of the text itself. The most famous work in which the English translation mauled the original French is Journey to the Center of the Earth, but even that notorious case pales beside the mauling received by Deux ans de vacances, to the material detriment of the story itself. (And Deux ans de vacances has nothing like JCE's volcanoes and dinosaurs to pierce through the gloom of a bad translation.)

It starts with the title itself. Titles were often changed in order (apparently) to make them more exciting; this hurts Deux ans de vacances much more than most others. Most of the story is, in fact, not about being 'adrift in the Pacific'; the boys are adrift in the Pacific for about three briefly described weeks, and then spend two years very much not adrift on a desert island. But the title was not just a label slapped onto the book; the last several paragraphs of the work in French are devoted to explaining, explicitly, why Verne chose that title in particular, so anyone who changes the title has already committed to changing how the book actually ends. But it is far worse than that. The dominant translation in English cuts out significant sections of the book, thus throwing off the structure, and sometimes takes the freest and most outrageous liberties with the text, nominally in order to make it more interesting to English-speaking boys. And worst of all is the fact that the translation (like not a few American translations of foreign authors in the nineteenth century) makes the work jarringly racist to read. Moko is black; he is also explicitly presented as one of the pillars in the boys' society because he is, next to Briant, the boy with the most relevant experience, due to his being a cabin boy. The boys mirror the societies of their parents, so Verne has explicitly put in a racial tinge on one or two points. Moko doesn't vote when the boys pick a leader, and the attitude of some of the boys toward him is a bit condescending (Doniphan most notably, although Doniphan is condescending in one way or another with everyone); but in the boys' society you can see the absurdity of Moko's lack of franchise. But that's the limits of Verne's engagement with racial issues. It is worlds away from the English translation. In Verne's tale, Moko calls Briant 'Mr. Briant' because he's a cabin boy, and that's how cabin boys speak to people who are in charge. In the English translation, Moko calls Briant 'Massa Briant' because Moko is black. That alone tells you everything you need to know.

So the only really available English translation of the work is atrocious. It's a pity, because the story itself is quite a good contribution to the genre of Robinsonade: a tale of how "order, zeal, and courage" can overcome in any situation, however dangerous.

Scottish Poetry XI

Horace. Book II. Ode X.

Rectius vives, Licini

by James Beattie

Wouldst thou through life securely glide;

Nor boundless o'er the ocean ride;

Nor ply too near th' insidious shore,

Scar'd at the tempest's threat'ning roar.

The man, who follows Wisdom's voice,

And makes the golden mean his choice,

Nor plung'd in antique gloomy cells

Midst hoary desolation dwells;

Nor to allure the envious eye

Rears his proud palace to the sky.

The pine, that all the grove transcends,

With every blast the tempest rends;

Totters the tower with thund'rous sound,

And spreads a mighty ruin round;

Jove's bolt with desolating blow

Strikes the ethereal mountain's brow.

The man, whose steadfast soul can bear

Fortune indulgent or severe,

Hopes when she frowns, and when she smiles

With cautious fear eludes her wiles.

Jove with rude winter wastes the plain,

Jove decks the rosy spring again.

Life's former ills are overpast,

Nor will the present always last.

Now Phoebus wings his shafts, and now

He lays aside th' unbended bow,

Strikes into life the trembling string,

And wakes the silent Muse to sing.

With unabating courage, brave

Adversity's tumultuous wave;

When too propitious breezes rise,

And the light vessel swiftly flies,

With timid caution catch the gale,

And shorten the distended sail.

Sunday, June 10, 2018

Scottish Poetry X

To the Nightingale

by Robert Allan

Sweetest minstrel, who at even,

Sheltered in thy leafy bower,

As the zephyrs sleep around thee,

Charm'st the balmy tranquil hour;

But when morning's beam is breaking,

And its lights around thee play,

Songster, then I list with sorrow

Thy last warblings die away.

From thy shade of fragrant blossoms

On night's ear thou pour'st thy strain,

While fond lovers, loth to leave thee,

Sigh to hear those strains again,_

And when autumn's blast, despoiling

All the sweets that deck thy spray,

Songster, then I list with sorrow

Thy last warblings die away.

Cease not yet thy song, sweet warbler,

Northy rosy bower forsake;

Lull the night to balmy slumbers,

Till the morning herald wake.

Slowly from the wild departing,

Slowly wending home my way,

Songster, then I list with sorrow.

Thy last warblings die away.