In the fifth century, Athens began to enter a golden age of prosperity and strength, and the inevitable happened: people started coming to Athens. New ways of thinking that had developed at the edge of the Greek world began to come together here, interacting with both each other and traditional Athenian ideas. The mixture was sometimes rather volatile. When the Ionian philosopher Anaxagoras came to Athens, he was accused of impiety (apparently for saying that the sun was not a god but a burning rock) and had to flee the city.

Into this mix stepped the Sophists. The original Sophists were all from outside of Athens -- Protagoras and Prodicus were from Ionia, Gorgias from Sicily. They came proposing to teach Athenian youths everything they needed to know in order to become successful in the thriving democratic society of Athens. Putting their achievement in the most positive light, we can say that they were serious proponents of democracy; they taught anyone, regardless of background, as long as they paid. They were also educational innovators. Prior to the Sophists students were educated by sunousia, that is, by just being hanging around with adults as the adults did their work, until they, too, had picked up the skills. The Sophists recognized that this was inefficient, and so began to develop artificial education: classrooms, lectures, and the like. These things cost more money than the sunousia method, but the major Sophists were all very good at what they did: teaching the things you needed to know to become powerfully persuasive in the assemblies of Athens. So people paid.

There were reactions. Some people thought the Sophists were just stirring up trouble; they were occasionally banned from cities. But the most important reaction for philosophical purposes took a different direction entirely. This reaction was spearheaded by Socrates. Socrates held that there were fundamental flaws in the Sophists' approach to education. Knowledge was not a list of formulas, not a set of tips and tricks; it was not something that could be bought or sold, nor could it be put into a student's mind by a teacher. The role of a teacher on Socrates' view was to play midwife: the student's mind, pregnant with truth, must bring it forth itself; the teacher does not give the student the truth any more than the midwife gives the mother the baby, but instead helps to make it easier for the mother to do the hard work of brining a new child into the world. Likewise, in education the student does all the discovery: the teacher just helps make the discovery happen more smoothly. Moreover, everyone benefits from the student's discovery, so Socrates did not believe in charging fees for teaching.

Socrates died in 399 BC. His students, however, spread out all over the Greek world, founding schools, usually on Socratic principles. There were many such schools founded, but one outshines them all: Plato's. Plato founded his school at the Grove of Akademos; because of that, it became known as the Academy. There are two reasons why Plato is the most important of all of Socrates's students:

(1) The Academy outlasted all other schools founded by the students of Socrates. It had an excellent location, was organized in a way that made it very flexible, and became the preeminent example of a philosophical institution.

(2) Plato was an extraordinarily good writer, and his philosophical dialogues are true masterpieces of Greek literature and thought. Other students had written Socratic dialogues, but we only have fragments of them; except for some dialogues by Xenophon that have also survived, Plato's dialogues are the only ones that survive in full.

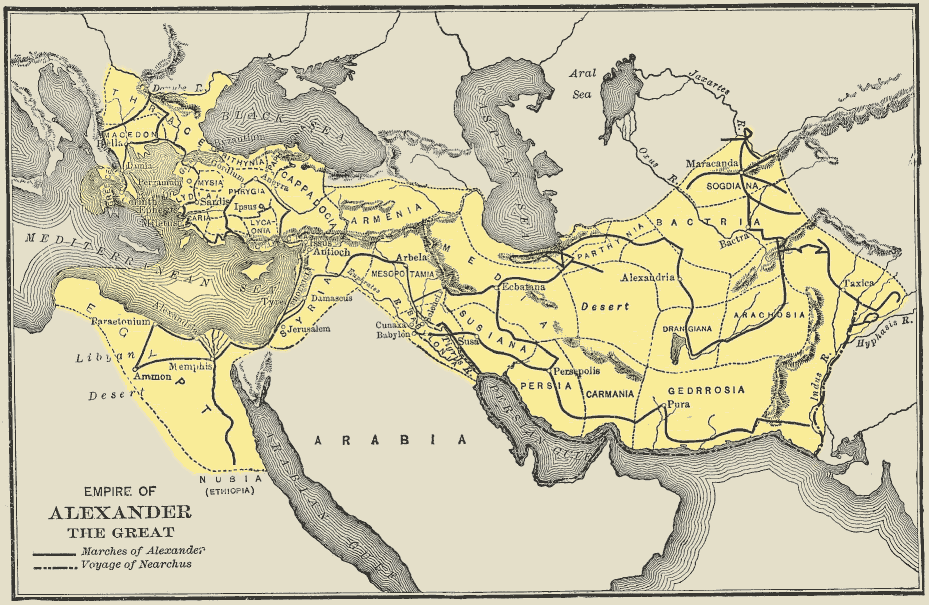

Plato had many students, but the most famous is Aristotle. Unlike Plato and Socrates, he was not Athenian; he was Macedonian, in fact. At one point he even tutored the son of the king of Macedonia. The son of the king of Macedonia was named Alexander, and he went on to conquer much of the known world. Because of this he was called Alexander the Great.

With Alexander the Great, however, we enter the Hellenistic period of philosophy.