* How to make a basic wire recorder. Wire recorders were the predecessors of tape recorders; instead of magnetic tape they worked by magnetizing hair-thin chromium-steel (i.e., stainless steel) wire. The wire didn't have the recording range of later magnetic tapes (limited bandwidth, I believe), being good enough for voice recording but relatively poor for much music recording. (However, the quality could still be fairly decent; here's a YouTube clip of a decent quality wire recording of music.) It was also a temperamental technology, inclined to snarl or snap at the slightest problem. On the other hand, higher quality recording wire is far more durable than magnetic tape. As with magnetic tape, the recording can be magnetically scrambled, but recording wire is much less sensitive to stray magnetic fields; recording wire corrodes, but far more slowly than magnetic tape deteriorates. The serious disadvantage of wire over tape, however, is that it requires a fairly fast recording speed: you go through wire much faster than through magnetic tape. This is why the wire is always ultra-fine, despite the problem of breakage: for anything more than very short recording you need thousands of feet of it.

I suspect that if you couldn't find real recording wire that you could adapt 40 gauge stainless steel ribbon to the purpose.

* I very much liked this essay by Meir Soloveichik on why Jonah is the primary reading for Yom Kippur.

* John Farrell on people placing Darwin in the bogey man role.

* The Grand Taxonomy of Rappers' Names

* Terry Pratchett forged his own sword to celebrate his knighting. That's exactly the right way to do it.

* Speaking of which, I recently read Pratchett's Small Gods in the Discworld series; it struck me as pretty much all of Pratchett's works strike me -- a lot of trite, banal, overused jokes such as one might hear in any lively pub in the world, strung together loosely into a story. Don't get me wrong. The sort of thing Pratchett is doing, satirical fantasy, is extremely difficult, and the result is inevitable: humorous satire and parody must be recognizable but fantastic settings reduce the recognizability, meaning that pretty much the only way one can pull it off is to have one's humor consist entirely of the most recognizable and obvious kinds of jokes. That Pratchett is actually a good author, and manages to rise well above what he is sometimes in danger of being, the Dan Brown of people who like to pretend that they are more clever and witty than they are, is seen in the fact that he often does manage to make the story itself come together in an artful and funny way. But it did start me thinking about one of the trite tropes he uses, the gods getting their power from human belief; and it made me wonder where that started. It's a very common fantasy trope these days. The commonness is easy enough to see the explanation of: it was spread by role-playing games and their assorted associated media. Dungeons & Dragons and things inspred thereby. But was that the origin? Are there cases earlier than D&D? (The TVTropes link makes some suggestions, few of which are actually plausible.)

* Martin Cothran has a rousing defense of Chesterton's philosophical acumen. One of the signs (neither necessary nor sufficient, but nonetheless a genuine sign) that there is more to Chesterton than meets the eye is that even people who have radically different views than he did are often impressed. Cothran mentions Shaw, of course; but there is a long list of others. One thinks immediately of Martin Gardner arguing repeatedly that "The Ethics of Elfland" was one of the most insightful post-Humean works in philosophy of science -- a claim that, however surprising, is more easily defended than you might think.

* I don't know if most of my readers now this, but one of my specializations is the problem of the external world; I wrote my thesis on Malebranche's account of our knowledge of whether the external world exists, and that thesis was (and still is, although in a very on-again-off-again way) part of a larger project of understanding different transformations of the problem in Malebranche, Berkeley, Hume, and Shepherd. So I found this comic quite funny.

ADDED LATEr

* So a couple of days ago Ahmadenijad was soapboxing in the UN and accused the US of being behind the Sept 11 attacks; the US diplomats walked out in the middle of the speech, which was the right thing to do -- there are better uses of our diplomats' time. But the list of the delegations that followed the US in walking out is interesting: Canada and all twenty-seven members of the European Union, Australia and New Zealand, and Costa Rica. (There are possibly one or two others; reports give a vague 'at least 33 delegations'. And not all delegations were present -- the Israeli delegation, for instance, was absent, officially for Sukkot, although there seems to be a widespread belief that there were additional reasons.)

Saturday, September 25, 2010

Thursday, September 23, 2010

Tension in the Mind

My citing the creation of tension as part of the work of the nonviolent resister may sound rather shocking. But I must confess that I am not afraid of the word "tension." I have earnestly opposed violent tension, but there is a type of constructive, nonviolent tension which is necessary for growth. Just as Socrates felt that it was necessary to create a tension in the mind so that individuals could rise from the bondage of myths and half truths to the unfettered realm of creative analysis and objective appraisal, so must we see the need for nonviolent gadflies to create the kind of tension in society that will help men rise from the dark depths of prejudice and racism to the majestic heights of understanding and brotherhood.

Martin Luther King, Jr., Letter from a Birmingham Jail. In my ethics class today we discussed the underlying ethical assumptions of the letter; on skimming it again before class, this passage, which I usually haven't paid close attention to, jumped out at me a bit.

Wednesday, September 22, 2010

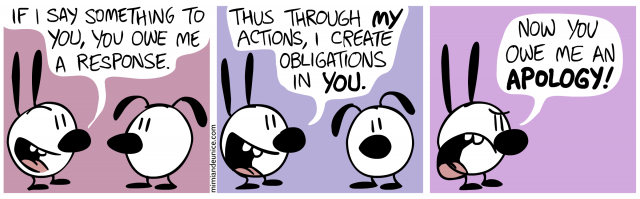

The Mimi Theory of Obligations of Discourse

Eunice, on the other hand, apparently agrees with me that obligations of discourse must be agreed upon.

Wordsworthian Poetics as Philosophical Method

It's generally recognized that Coleridge had an ambition to be a philosophical poet; it seems to be less remarked that Wordsworth did as well. In some sense, Coleridge's philosophy is obvious: it's German philosophy adapted to Coleridge's particular tastes. Wordsworth is just as philosophical as Coleridge, however; he is simply less obvious about it. It is also true that his particular philosophical approach is in itself not immediately the sort of thing that comes to mind when one thinks of philosophy.

Wordsworthian poetry is very sentiment-oriented (it was almost certainly this aspect of it that helped J. S. Mill out of his nervous depression). But it is not the less philosophical in aim for being sentimental in means. As Wordsworth puts it in the Preface to the Lyrical Ballads:

This poetic search for the self-authenticating face of truth is where sentiment comes into play: the Wordsworthian poet attempts to portray things with, as he says elsewhere in the Preface, a "colouring of the imagination," so that even ordinary things become striking, thereby, as he says here, to carry the truth "alive into the heart by passion." The poet does this by respecting the principles of association at the basis of the imagination, particularly insofar as they govern the mind in a state of genuine excitement, one that follows from our perception of the like in the unlike and the similar in the different. Poetry attempts to capture something of this excitement of the strangely familiar and familiarly strange world, recollecting the feel of it in a quiet moment ("emotion recollected in tranquillity" until it becomes vivid and living again). This pursuit of what pleases is itself supposed to be philosophical:

One of the primary tasks of the poet, if this is true, is to capture things we already know about the world, but make us realize them anew, as the exciting and interesting things they are. The poet drives our interest in the world as fitting to the human mind, and in the human mind as fitting to the world: he therefore captures the very essence of inquiry, and makes poetry "he breath and finer spirit of all knowledge" and "the impassioned expression which is in the countenance of all Science". The poet takes science and knowledge and makes them genuinely human things; a necessary function, without which most people will necessarily be shut off from them.

All of this does have the implication that poetry deals with appearances, not realities; as he says in the supplementary Essay of 1815, it concerns itself with things "not as they exist in themselves, but as they seem to exist to the senses, and to the passions". This does have a potential danger: poetry is spontaneous overflow of emotion, yes, but it is spontaneous overflow within the context of disciplined understanding and reason. The common failure to recognize this makes it difficult to recognize true poetic genius, the kind that makes poetry a companion and indeed mother of knowledge:

Poetic genius -- and Wordsworth clearly counts himself (and not incorrectly, it must be said) -- unites past and future: all our sentiments and passions, which have been in us for all of human history, clothe even the most up-to-date knowledge in striking form, intimating new approaches. It exhibits "that accord of sublimated humanity which is at once a history of the remote past and a prophetic enunciation of the remotest future" and therefore is rarely appreciated in the present.

Wordsworthian poetics, then, is not just verse but a method of philosophical description, whereby one attempts to express the features of the world in the way most suitable and appropriate to the human mind, and to express the features of the human mind in the way most appropriate to their interaction with the world; it manages this by basing itself on actual experience of the world. In experience the world we sense and feel; and the feelings and emotions with which we experience the world can be re-captured by a means of description that takes into account the minds own processes of association and uses them to put the mundane in a striking light. We re-experience, but in a sense we do so by again experiencing it for the first time. This paradox is rooted in the fact that the poet uses similarities and dissimilarities, likenesses and unlikenesses, to describe the world we have already experienced; this brings it again to mind and in a way that leads us to recognize again things we have perhaps forgotten or come to take for granted.

We tend, of course, to think of philosophy as concerned with good arguments; but there is an excellent case for saying that good description is also essential to it. If nothing else, otherwise good arguments regularly run aground by being based on poor and misleading descriptions of the world. And description, too, can shade into argument. Wordsworth's Intimations of Immortality from Recollections of Early Childhood is not often recognized as an argument for the immortality of the soul, but it is. Wordsworth somewhere explicitly talks about the elevations of the sentiments and the affections toward eternity that are produced by faith as a "presumptive evidence of a future state of existence" and the ode is itself an attempt to describe those features of childhood experience that intimate our suitability for life beyond this mortal frame of nature, those features of our lives that give meaning to the idea that we seem to be fit for something more. It is a philosophical argument. It is, however, a philosophical argument built on extraordinarily subtle aspects of our experience; capturing these properly in description is beyond the ability of most people we think of as philosophers. It is a purely philosophical argument that only a master poet could write.

Philosophers, and certainly philosophers today, are not taught to pay attention to intimations, so proper presentation of an argument that is based on intimations is not something most philosophers can do. Trying to remedy this was one of the primary goals of the Romantic philosophers, who argued that poetry, science, and philosophy must come together. It is this that makes Wordsworth a Romantic poet. And it is this that makes Wordsworth a Romantic philosopher.

Wordsworthian poetry is very sentiment-oriented (it was almost certainly this aspect of it that helped J. S. Mill out of his nervous depression). But it is not the less philosophical in aim for being sentimental in means. As Wordsworth puts it in the Preface to the Lyrical Ballads:

Aristotle, I have been told, has said, that Poetry is the most philosophic of all writing: it is so: its object is truth, not individual and local, but general, and operative; not standing upon external testimony, but carried alive into the heart by passion; truth which is its own testimony, which gives competence and confidence to the tribunal to which it appeals, and receives them from the same tribunal. Poetry is the image of man and nature.

This poetic search for the self-authenticating face of truth is where sentiment comes into play: the Wordsworthian poet attempts to portray things with, as he says elsewhere in the Preface, a "colouring of the imagination," so that even ordinary things become striking, thereby, as he says here, to carry the truth "alive into the heart by passion." The poet does this by respecting the principles of association at the basis of the imagination, particularly insofar as they govern the mind in a state of genuine excitement, one that follows from our perception of the like in the unlike and the similar in the different. Poetry attempts to capture something of this excitement of the strangely familiar and familiarly strange world, recollecting the feel of it in a quiet moment ("emotion recollected in tranquillity" until it becomes vivid and living again). This pursuit of what pleases is itself supposed to be philosophical:

It is an acknowledgement of the beauty of the universe, an acknowledgement the more sincere, because not formal, but indirect; it is a task light and easy to him who looks at the world in the spirit of love: further, it is a homage paid to the native and naked dignity of man, to the grand elementary principle of pleasure, by which he knows, and feels, and lives, and moves....We have no knowledge, that is, no general principles drawn from the contemplation of particular facts, but what has been built up by pleasure, and exists in us by pleasure alone.

One of the primary tasks of the poet, if this is true, is to capture things we already know about the world, but make us realize them anew, as the exciting and interesting things they are. The poet drives our interest in the world as fitting to the human mind, and in the human mind as fitting to the world: he therefore captures the very essence of inquiry, and makes poetry "he breath and finer spirit of all knowledge" and "the impassioned expression which is in the countenance of all Science". The poet takes science and knowledge and makes them genuinely human things; a necessary function, without which most people will necessarily be shut off from them.

All of this does have the implication that poetry deals with appearances, not realities; as he says in the supplementary Essay of 1815, it concerns itself with things "not as they exist in themselves, but as they seem to exist to the senses, and to the passions". This does have a potential danger: poetry is spontaneous overflow of emotion, yes, but it is spontaneous overflow within the context of disciplined understanding and reason. The common failure to recognize this makes it difficult to recognize true poetic genius, the kind that makes poetry a companion and indeed mother of knowledge:

Genius is the introduction of a new element into the intellectual universe: or, if that be not allowed, it is the application of powers to objects on which they had not before been exercised, or the employment of them in such a manner as to produce effects hitherto unknown. What is all this but an advance, or a conquest, made by the soul of the poet? Is it to be supposed that the reader can make progress of this kind, like an Indian prince or general—stretched on his palanquin, and borne by his slaves? No; he is invigorated and inspirited by his leader, in order that he may exert himself; for he cannot proceed in quiescence, he cannot be carried like a dead weight. Therefore to create taste is to call forth and bestow power, of which knowledge is the effect; and there lies the true difficulty.

Poetic genius -- and Wordsworth clearly counts himself (and not incorrectly, it must be said) -- unites past and future: all our sentiments and passions, which have been in us for all of human history, clothe even the most up-to-date knowledge in striking form, intimating new approaches. It exhibits "that accord of sublimated humanity which is at once a history of the remote past and a prophetic enunciation of the remotest future" and therefore is rarely appreciated in the present.

Wordsworthian poetics, then, is not just verse but a method of philosophical description, whereby one attempts to express the features of the world in the way most suitable and appropriate to the human mind, and to express the features of the human mind in the way most appropriate to their interaction with the world; it manages this by basing itself on actual experience of the world. In experience the world we sense and feel; and the feelings and emotions with which we experience the world can be re-captured by a means of description that takes into account the minds own processes of association and uses them to put the mundane in a striking light. We re-experience, but in a sense we do so by again experiencing it for the first time. This paradox is rooted in the fact that the poet uses similarities and dissimilarities, likenesses and unlikenesses, to describe the world we have already experienced; this brings it again to mind and in a way that leads us to recognize again things we have perhaps forgotten or come to take for granted.

We tend, of course, to think of philosophy as concerned with good arguments; but there is an excellent case for saying that good description is also essential to it. If nothing else, otherwise good arguments regularly run aground by being based on poor and misleading descriptions of the world. And description, too, can shade into argument. Wordsworth's Intimations of Immortality from Recollections of Early Childhood is not often recognized as an argument for the immortality of the soul, but it is. Wordsworth somewhere explicitly talks about the elevations of the sentiments and the affections toward eternity that are produced by faith as a "presumptive evidence of a future state of existence" and the ode is itself an attempt to describe those features of childhood experience that intimate our suitability for life beyond this mortal frame of nature, those features of our lives that give meaning to the idea that we seem to be fit for something more. It is a philosophical argument. It is, however, a philosophical argument built on extraordinarily subtle aspects of our experience; capturing these properly in description is beyond the ability of most people we think of as philosophers. It is a purely philosophical argument that only a master poet could write.

Philosophers, and certainly philosophers today, are not taught to pay attention to intimations, so proper presentation of an argument that is based on intimations is not something most philosophers can do. Trying to remedy this was one of the primary goals of the Romantic philosophers, who argued that poetry, science, and philosophy must come together. It is this that makes Wordsworth a Romantic poet. And it is this that makes Wordsworth a Romantic philosopher.

How exquisitely the individual Mind

(And the progressive powers perhaps no less

Of the whole species) to the external World

Is fitted:--and how exquisitely too--

Theme this but little heard of among men--

The external World is fitted to the Mind;

And the creation (by no lower name

Can it be called) which they with blended might

Accomplish:--this is our high argument.

Knowledge for us is difficult to gain--

Is difficult to gain, and hard to keep--

As virtue's self; like virtue is beset

With snares; tried, tempted, subject to decay.

Love, admiration, fear, desire, and hate,

Blind were we without these: through these alone

Are capable to notice or discern

Or record: we judge, but cannot be

Indifferent judges.

Monday, September 20, 2010

Newman Links

* Roger Scruton talks Newman and the University.

* Miriam Burstein notes that Scruton's discussion leaves a few things out.

* And D. G. Myers raises the natural next question.

* James Martin notes that October 9, the day chosen for Newman's feast day, is significant. As the Suburban Banshee points out, though, there are straightforward practical reasons as well.

* Beatification of course means that Newman is given a limited liturgical role; the next step is canonization, which requires the addition of another sign. This investigation is already underway.

* Miriam Burstein notes that Scruton's discussion leaves a few things out.

* And D. G. Myers raises the natural next question.

* James Martin notes that October 9, the day chosen for Newman's feast day, is significant. As the Suburban Banshee points out, though, there are straightforward practical reasons as well.

* Beatification of course means that Newman is given a limited liturgical role; the next step is canonization, which requires the addition of another sign. This investigation is already underway.

Sunday, September 19, 2010

Offices of Kindness, Benevolence, and Considerateness

So it's now Blessed John Henry Newman. From one of his sermons, a passage that is always timely:

As Christians, we cannot forget how Scripture speaks of the world, and all that appertains to it. Human Society, indeed, is an ordinance of God, to which He gives His sanction and His authority; but from the first an enemy has been busy in its depravation. Hence it is, that while in its substance it is divine, in its circumstances, tendencies, and results it has much of evil. Never do men come together in considerable numbers, but the passion, self-will, pride, and unbelief, which may be more or less dormant in them one by one, bursts into a flame, and becomes a constituent of their union. Even when faith exists in the whole people, even when religious men combine for religious purposes, still, when they form into a body, they evidence in no long time the innate debility of human nature, and in their spirit and conduct, in their avowals and proceedings, they are in grave contrast to Christian simplicity and straightforwardness. This is what the sacred writers mean by "the world," and why they warn us against it; and their description of it applies in its degree to all collections and parties of men, high and low, national and professional, lay and ecclesiastical.

It would be hard, then, if men of great talent and of special opportunities were bound to devote themselves to an ambitious life, whether they would or not, at the hazard of being accused of loving their own ease, when their reluctance to do so may possibly arise from a refinement and unworldliness of moral character. Surely they may prefer more direct ways of serving God and man; they may aim at doing good of a nature more distinctly religious; at works, safely and surely and beyond all mistake meritorious; at offices of kindness, benevolence, and considerateness, personal and particular; at labours of love and self-denying exertions, in which their left hand knows nothing that is done by their right.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)