"Every classification has reference to a tendency toward an end. If this tendency is the tendency which has determined the class characters of the objects, it is a natural classification." C. S. Peirce

"Every unitary classification has a leading idea or purpose, and is a natural classification in so far as that same purpose is determinative in the production of the objects classified."

Peirce on the 'longitude' of final causes: "By this I mean that while a certain ideal end state of things might most perfectly satisfy a desire, yet a situation somewhat different from that will be far better than nothing; and in general, when a state is not too far from teh ideal state, the nearer it approaches that state the better." (CP 1.207)

typological classification and the longitude of final causes

cp. "clustering distributions will characterize purposive classes" (Peirce, CP 1.207).

"the fact that classes merge is no proof that they are not truly distinct classes" Peirce

Dave Oswald Mitchell on protest organizing

(1) Put target in a decision dilemma.

(2) Do the media's work for them (give them the story).

(3) Lead with sympathetic characters.

"Unjust and unlawful is any monopoly, educational and scholastic, which, physically or morally, forces families to make use of government schools contrary to the dictates of their Christian conscience." Pius XI

When we say that something works in a lawlike fashion, we mean that it does so as if its possibilities were constrained and weighted so as to select a result; that is final causation.

Roberts (2008): While theories may draw on laws, the function of being a law is not part of a scientific theory.

pseudonymous persona and quasi-property

"Not everyone who imagines something is also aware and judges that he has imagined." Avicenna

Steinkrüger (2015): Aristotle's logic is a relevance logic in the sense that (a) premises and conclusion must in some way share content and (b) premises must be used to derive the conclusion.

God as the truthmaker for 'Good is to be done and sought, and bad avoided'

natural a priori (mind prior to any experience), structural a priori (mind in making sense of experience to begin with), conceptual a priori (mind drawing on experience and going beyond it)

sensory a posteriori, memorial or memorative a posteriori, introspective a posteriori

Everybody accepts some philosophical claims on testimony.

felt alienness accounts of the external world

(perhaps more general as felt alterity, with alienness as an extreme form)

Because of the way utilitarianism is structured, utilitarianism tends toward catastrophe-mining.

Philosophical rhetoric studies possible means of persuasion -- the 'possible' is important.

Whewellian superinduction of concepts and the synthetic a priori

"We have a human need to pray in a way that overwhelms our senses, and the human need to have that experience interpreted to us so that it becomes even richer and fuller and more significant, because worship is not an individual act but a communal event." Cat Hodge

Ganeri (2003): Nyaya logic as case-based reasoning

"Even plants have things done to them that are harmful or beneficial, and what does them good must be related in some way to their living and dying." Philippa Foot

Goldman's account of sexual desire in "Plain Sex" ("desire for contact with another person's body and for the pleasure which such contact produces") massively oversexualizes the desire for bodily contact and fails to recognize the distinctness of it from the desire to give pleasure and similar desires.

What we usually call political parties are not parties as such but organizational shells for them.

A philosophical system is a unified interpretation of arguments.

Some subarguments are within the universe of the main argument (direct reasons for premises); others are in a universe modally related (reductio & hypothetical 'suppose x' arguments generally).

The spirit of moral laws is not confined to some purely interior disposition but is a matter of the disposition of one's whole life.

"No man can possibly be righteous without having the hope, from the analogy of the physical world, that righteousness must have its reward." Kant

The very idea of making suggests the question of whether the world is made and what, if it is, makes it.

Spatial metaphors typically capture modal information.

"All men are certain that there is an external world: and yet they have not this certainty from their consciousness, for consciousness is limited to phenomena purely internal; nor do they know the fact by evidence, because, even supposing the possibility of a true demonstration, many would be incpaable of comprehending it, and because the majority have never thought, and never will think, of such demonstrations." Balmes

Balmes's common sense is a sense of the extravagantness of a possibility; by it we recognize that some possibilities, despite being possibilities, are too extravagant to be true, that something seems too unlikely to be taken seriously. This is fallible, he thinks, unless four features are found in it:

(1) the impulse is irresistible

(2) it is plausible to treat it as common to the whole human race

(3) it endures tests of reason

(4) it bears on the satisfaction of some fundamental need of all human life.

four kinds of impossibility (Balmes)

(1) metaphysical: implies contradiction

(2) physical: violates law of nature

(3) ordinary/moral: violates ordinary course of things

(4) of common sense: too improbable by its very nature ever to be verified

"In reading, there are two essentials: to select good books, and to read them well." Balmes

"It is only when perception fails us that we have to ask the question whether a thing is so or not." Aristotle

"Love, recognizing germs of loveliness in the hateful, gradually warms it into life, and makes it lovely." Peirce

Law does not govern external action only; it also gives people a guideline to keep in mind in relating to others.

moral regards: self-reflective, cooperative, abstract, regulative

each idea a silkworm for the magnaneries of reason

Representations are activations.

The brain is an organ of sensory representation.

Whether logical truths exclude possibilities depends on the specific modalities being considered.

(1) paradigmatics

(2) formal model construction

(3) history of philosophy

(4) evidential analysis

(5) socratics

Jurisprudence does not ignore internal disposition; its means of taking it into account are limited, but they are important. (Consider, for instance, the roles of 'malice', 'insanity', 'sincerity', 'mental anguish', and the like.)

term contradiction

syllogistic reduction as a practice for students on the way to doing proofs fully

Martin (1993): "To fathom the nature of etiquette, one must realize that etiquette plays at least three distinct, conceptually separable social functions: a regulative, a symbolic, and a ritual function."

-- law cannot be justly administered without etiquette

-- "In its symbolic function, etiquette provides a system of symbols whose semantic content provides for predictability in social relations, especially among strangers."

(1) There are no degrees of belief, properly speaking.

(2) The language usually used to suggest there are does not, and could not, support degrees of belief being real-valued.

(3) There is no reason to think that degrees of belief would have to correspond to odds for betting on propositions.

'Popular antiquities' should have been kept as a subgenus of 'folklore'.

'personal brand' as quasi-property

person ) persona ) personal brand (persona instrumentality)

natural religion as seal of ethics

Liguori on baptism of desire: Moral Theology Bk 6 nn 95-97

-- note that he takes it to be de fide (Council of Trent session 6, chapter 4: 'sine lavacro regenerationis aut ejus voto')

fluminis, flaminis, sanguinis

grace as that whereby we imitate God and converse with him.

"A benevolent judge is unthinkable." (Kant)

-- a great deal about Kant in this one sentence

Democracy obscures the courses of power by allowing power to be exercised anonymously through intermediary networks built for that purpose; thus with it, one always has to consider the behind-scenes.

If 'best scientific view' includes our best scientific accounts of all major domains, our best scientific view is at any given moment incoherent.

reason's title to inquire

Even the most prudent people require advice, and even at times clarification of principles and moral concepts, or morally relevant concepts, that another can more easily provide.

freedom as "that faculty which gives unlimited usefulness to all other faculties" (Kant)

the duty of ordering one's life so as to be fit for the performance of moral duties

consciousness of one's life as a trust

moral luck // intellectual luck

We use metaphors not only to get people to notice things, but also to get them not to notice things, i.e., to obscure things. One can perhaps treat the latter as sleight-of-indication, misdirecton taht is trying to get people to notice something else, but these are also not exhaustive, and also shared with literal discourse.

mathematical insulation: there is no way to unite all of math into a single system without insulating some parts from some other parts

Rigor is a relation of means to end.

"All nations begin with theology and are founded by theology." Maistre

"The beautiful, in all imaginable genres, is that which pleases enlightened virtue. Any other definition is false or insufficient." Maistre

Secularization proceeds by active resource denial on one side and active retreat on the other.

NB Xiong's argument that we assume external objects because we become accustomed to relying on things for nourishment.

genuine liberal Christianity vs. neochristianity

a mind rich with folds

While Wittgenstein talks about 'hinge' propositions, it would perhaps be more reasonable to talk of envelope propositions.

subject, world, and God as postulates of philosophical inquiry

The notion of cause is at the heart of our notion of the world; without causes there is no world.

"Observation and experience show that a worthless man values his life more than his person." Kant

philosophical problems as loci for debates

Evidence-collection is structured by choices.

the rights of refuge of victims of wreck (shipwreck, plane crashes, storms and other catastrophes forcing to shelter) vs the rights of refuge of people in flight

Saturday, May 02, 2020

Friday, May 01, 2020

Evening Note for Friday, May 1

Thought for the Evening: Modes of Reference in Rituals

In a paper that should be better known, "Modes of Reference in the Rituals of Judaism" [Religious Studies, Vol. 23, No. 1 (Mar., 1987), pp. 109-128], Josef Stern applied some ideas of Nelson Goodman's theory of symbols in art to various Jewish rituals (as you might expect from the title). I'm not especially impressed by Goodman's account in general, but Stern, I think, does a good job of capturing what is of value in it.

Goodman takes symbols to be primarily constituted by reference, in which they stand for something; but there are different ways things can stand for something. There are several, but two notable ones are denotation, in which something like a description or a word attributes something to something as the possession of the latter, and exemplification, in which the symbol possesses that to which it refers and thus exhibits it, like a sample of something.

What Stern does is take this and apply the ideas to "ritual gestures", by which he means "all actions and objects that achieve ritual status" (p. 109). Judaism, of course, is very ritual-rich. The ritual gestures of Judaism do not merely act as symbols, but they do act as symbols of various kinds. When we look out how these ritual gestures refer, we get several varieties, which are sometimes found in simple forms but sometimes mixed in complex ways.

(1) Representation, which is essentially denotation. A typical case of this is the ritual gesture that is a commemoration. Circumcision, for instance, commemorates the covenant of Abraham by way of Scriptural authority; there is nothing particularly about circumcision itself that suggests Abraham or covenants, but Scriptural authority sets a precedent and a standard for its use as a way to refer to the Abrahamic covenant in order to bring it to mind. Others might do so in a way that's more 'pictorial', like haroset at Passover, which commemorates slavery in Egypt; a paste of fruits and nuts, its muddy color and texture is a sort of pictorial representation of mortar for bricks. Yet others might do so more metaphorically or metonymically, by depicting or suggesting something related to or like that to which they refer.

(2) Exemplification. Exemplification is not complete reiteration; as a symbolic mode of reference it generally takes a little something (we might say) that is of the same type as what it refers to. Stern's example is that Israel is commanded (Dt 26:2) to bring every first fruit; given that this is, if taken hyperliterally, usually impracticable, and given that offering first fruits is by its nature a symbolic offering anyway, the Rabbis have generally taken this to mean that you should bring first fruits capable of representing every first fruit, namely, the seven specifically mentioned in Deuteronomy 8:8. All of these are actually first fruits, but they also stand for all first fruits whatsoever.

(3) Expression, which is a form of exemplification that works figuratively. Bowing at the beginning of the benedictions of the Amidah expresses homage. It does not do so because the person bowing has feelings of homage. In fact, it is the reverse: the point of the bowing is to put the person bowing in a state of mind that is at least suitable to such feelings.

All three of these are often found in combination. Take representation and exemplification. "While denotation is the preponderant mode of reference for (verbal) languages, and exemplification is more central to the arts, the two frequently function in tandem in ritual gestures" (p. 112). The bitter herbs of Passover both exemplify the bitter herbs used in the ancient Passovers and also commemorate the sudden flight from Egypt, and this is quite common; indeed, the interaction between these two modes of reference often lead to further symbolizations associated with them. This leads to the forming of symbol-chains, which give to ritual a living flexibility.

While these three are in some way fundamental, there are other kinds of reference in which ritual gestures refer to other, parallel ritual gestures.

(4) Allusion. One ritual may have reference to another; Stern notes that the rabbis will sometimes explain a Sukkot ritual by a Shavuot ritual. Another example that he doesn't use is that there's a lot of evidence that early Hanukkah rituals were modeled on Sukkot rituals; Hanukkah, the feast of dedication, was a relatively new celebration, and as it was a joyful celebration for the people, it was done by partial imitation of the major festival that was both joyful and popular in its actual celebration, namely, Sukkot, the festival of tabernacles. But it's not as if the early ritual gestures were just direct copies; they were adaptations to different purposes, and the rituals were modified accordingly, sometimes quite heavily.

(5) Re-enactment. A re-enactment is a token of the same type as that to which it refers, so as to be a successor to it in a series. Thus a Sabbath ritual gesture, which commemorates Creation, is also a re-enactment of previous Sabbath ritual gestures. A Passover seder is both a commemoration of the Exodus and a re-enactment of past Passover seders going back to the original.

(6) However, perhaps the most important way in which a ritual gesture would refer to others, is one for which Stern doesn't settle on a name but which we might call Co-participation. In the Passover seder there is a recitation of the Haggadah. The Haggadah commemorates the Exodus both by description and by dramatic portrayal; it is an exemplification of the kind of thing that is commanded to be done for Passover in Exodus 13:8; it re-enacts previous recitations; but it does something more. The Haggadah represents those participating in the seder as in some way involved with the Exodus itself. This goes beyond commemoration in the ordinary sense. The way Stern tries to explain this is by suggesting that this is tied up to the nature of the ritual as a story, and in particular as a story of stories. Storytelling of the sort that is expected in the seder is not simply a description, but an imaginative appropriation; but the Haggadah doesn't simply tell the participants to do this, it walks the participants through it, in going through samples of how prior generations did this. And in participating in the recitation in this way, the participant is also participating in the community of all those who have done this in the past. "Through this mode of symbolization, the Exodus thus serves, not only as the historical beginning of the nation of Israel, but as an imaginative origin by which the Jewish community is regularly recreated through its performance of ritual" (p. 128).

This is not necessarily a perfectly exhaustive list, although obviously it covers a great deal. But the strength of it lies in its generalizability.

Various Links of Interest

* A Close Look at the Frontrunning Coronavirus Vaccines As of April 23

* At the Journal of the History of Philosophy:

Anselm Spindler, Politics and Collective Action in Thomas Aquinas's On Kingship

Deborah Boyle, Mary Shepherd on Mind, Soul, Self

Edward Slowik, Cartesian Holenmerism and Its Discontents

Lawrence Pasternack, Restoring Kant's Conception of the Highest Good

Dario Perinetti, Hume at La Flèche

Terry Echterling, What Did Glaucon Draw?

* Étienne Brown, Kant’s Doctrine of the Highest Good: A Theologico-Political Interpretation

* Tyler Hildegrand, Non-Humean Theories of Natural Necessity

* Nathan Pinkoski, How Not to Challenge the Integralists

* Charles De Koninck, The End of the Family and the End of Civil Society

* Gordon Graham, Scottish Philosophy in the 19th Century, at the SEP

* Snail salves, waters, & syrups at "Early Modern Medicine"

* Gray Connolly, The Geopolitical Lessons of 2020

* Thomas Pink, Suarez on Authority as Coercive Teacher

* The Impossibility of Language Acquisition, an interesting semi-interview with language research pioner Lila Geitman, was a really enjoyable look at the issues in studying language acquisition.

* Kelsey Donk looks at some of the likely effects of the shutdowns on our food supply. Briefly and roughly: most of what we have seen so far has been due simply to adjustment problems, given that we have distinct commercial and grocery food distribution systems and it is very difficult to switch from one to the other; we are not anywhere near a real shortage, since the problem is that we are actually having gluts that we can't sell because we can't distribute them to the people who are buying. These problems will slowly be solved by various sorts of improvised solutions. But food production has to be planned about a year ahead based on what we can do now; as what farmers can do now massively contracts due to distribution problems and the like, we will likely see the effects starting in February of next year. If the lockdowns don't last a long time, the problems will likely be minor disruptions in the U.S. -- milk might become very expensive, bacon might be almost impossible to get, some things might have roller coaster prices or go in and out of availability. Food distribution brownouts, so to speak. The reason they will be minor, however, is that the U.S. is a massive agricultural exporter; what is likely to happen is that we will use domestically what would usually be sold abroad. Since other exporting nations will likely do the same, nations that are less agriculturally self-sufficient -- and there are a lot -- will find their domestic production stretched very thinly. Of course, a lot depends on decisions made between now and next year as to how serious that will become.

Currently Reading

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, The Hound of the Baskervilles

Matthew C. Briel, A Greek Thomist: Providence in Gennadios Scholarios

Stephen Jarvis, Death and Mr. Pickwick

In a paper that should be better known, "Modes of Reference in the Rituals of Judaism" [Religious Studies, Vol. 23, No. 1 (Mar., 1987), pp. 109-128], Josef Stern applied some ideas of Nelson Goodman's theory of symbols in art to various Jewish rituals (as you might expect from the title). I'm not especially impressed by Goodman's account in general, but Stern, I think, does a good job of capturing what is of value in it.

Goodman takes symbols to be primarily constituted by reference, in which they stand for something; but there are different ways things can stand for something. There are several, but two notable ones are denotation, in which something like a description or a word attributes something to something as the possession of the latter, and exemplification, in which the symbol possesses that to which it refers and thus exhibits it, like a sample of something.

What Stern does is take this and apply the ideas to "ritual gestures", by which he means "all actions and objects that achieve ritual status" (p. 109). Judaism, of course, is very ritual-rich. The ritual gestures of Judaism do not merely act as symbols, but they do act as symbols of various kinds. When we look out how these ritual gestures refer, we get several varieties, which are sometimes found in simple forms but sometimes mixed in complex ways.

(1) Representation, which is essentially denotation. A typical case of this is the ritual gesture that is a commemoration. Circumcision, for instance, commemorates the covenant of Abraham by way of Scriptural authority; there is nothing particularly about circumcision itself that suggests Abraham or covenants, but Scriptural authority sets a precedent and a standard for its use as a way to refer to the Abrahamic covenant in order to bring it to mind. Others might do so in a way that's more 'pictorial', like haroset at Passover, which commemorates slavery in Egypt; a paste of fruits and nuts, its muddy color and texture is a sort of pictorial representation of mortar for bricks. Yet others might do so more metaphorically or metonymically, by depicting or suggesting something related to or like that to which they refer.

(2) Exemplification. Exemplification is not complete reiteration; as a symbolic mode of reference it generally takes a little something (we might say) that is of the same type as what it refers to. Stern's example is that Israel is commanded (Dt 26:2) to bring every first fruit; given that this is, if taken hyperliterally, usually impracticable, and given that offering first fruits is by its nature a symbolic offering anyway, the Rabbis have generally taken this to mean that you should bring first fruits capable of representing every first fruit, namely, the seven specifically mentioned in Deuteronomy 8:8. All of these are actually first fruits, but they also stand for all first fruits whatsoever.

(3) Expression, which is a form of exemplification that works figuratively. Bowing at the beginning of the benedictions of the Amidah expresses homage. It does not do so because the person bowing has feelings of homage. In fact, it is the reverse: the point of the bowing is to put the person bowing in a state of mind that is at least suitable to such feelings.

All three of these are often found in combination. Take representation and exemplification. "While denotation is the preponderant mode of reference for (verbal) languages, and exemplification is more central to the arts, the two frequently function in tandem in ritual gestures" (p. 112). The bitter herbs of Passover both exemplify the bitter herbs used in the ancient Passovers and also commemorate the sudden flight from Egypt, and this is quite common; indeed, the interaction between these two modes of reference often lead to further symbolizations associated with them. This leads to the forming of symbol-chains, which give to ritual a living flexibility.

While these three are in some way fundamental, there are other kinds of reference in which ritual gestures refer to other, parallel ritual gestures.

(4) Allusion. One ritual may have reference to another; Stern notes that the rabbis will sometimes explain a Sukkot ritual by a Shavuot ritual. Another example that he doesn't use is that there's a lot of evidence that early Hanukkah rituals were modeled on Sukkot rituals; Hanukkah, the feast of dedication, was a relatively new celebration, and as it was a joyful celebration for the people, it was done by partial imitation of the major festival that was both joyful and popular in its actual celebration, namely, Sukkot, the festival of tabernacles. But it's not as if the early ritual gestures were just direct copies; they were adaptations to different purposes, and the rituals were modified accordingly, sometimes quite heavily.

(5) Re-enactment. A re-enactment is a token of the same type as that to which it refers, so as to be a successor to it in a series. Thus a Sabbath ritual gesture, which commemorates Creation, is also a re-enactment of previous Sabbath ritual gestures. A Passover seder is both a commemoration of the Exodus and a re-enactment of past Passover seders going back to the original.

(6) However, perhaps the most important way in which a ritual gesture would refer to others, is one for which Stern doesn't settle on a name but which we might call Co-participation. In the Passover seder there is a recitation of the Haggadah. The Haggadah commemorates the Exodus both by description and by dramatic portrayal; it is an exemplification of the kind of thing that is commanded to be done for Passover in Exodus 13:8; it re-enacts previous recitations; but it does something more. The Haggadah represents those participating in the seder as in some way involved with the Exodus itself. This goes beyond commemoration in the ordinary sense. The way Stern tries to explain this is by suggesting that this is tied up to the nature of the ritual as a story, and in particular as a story of stories. Storytelling of the sort that is expected in the seder is not simply a description, but an imaginative appropriation; but the Haggadah doesn't simply tell the participants to do this, it walks the participants through it, in going through samples of how prior generations did this. And in participating in the recitation in this way, the participant is also participating in the community of all those who have done this in the past. "Through this mode of symbolization, the Exodus thus serves, not only as the historical beginning of the nation of Israel, but as an imaginative origin by which the Jewish community is regularly recreated through its performance of ritual" (p. 128).

This is not necessarily a perfectly exhaustive list, although obviously it covers a great deal. But the strength of it lies in its generalizability.

Various Links of Interest

* A Close Look at the Frontrunning Coronavirus Vaccines As of April 23

* At the Journal of the History of Philosophy:

Anselm Spindler, Politics and Collective Action in Thomas Aquinas's On Kingship

Deborah Boyle, Mary Shepherd on Mind, Soul, Self

Edward Slowik, Cartesian Holenmerism and Its Discontents

Lawrence Pasternack, Restoring Kant's Conception of the Highest Good

Dario Perinetti, Hume at La Flèche

Terry Echterling, What Did Glaucon Draw?

* Étienne Brown, Kant’s Doctrine of the Highest Good: A Theologico-Political Interpretation

* Tyler Hildegrand, Non-Humean Theories of Natural Necessity

* Nathan Pinkoski, How Not to Challenge the Integralists

* Charles De Koninck, The End of the Family and the End of Civil Society

* Gordon Graham, Scottish Philosophy in the 19th Century, at the SEP

* Snail salves, waters, & syrups at "Early Modern Medicine"

* Gray Connolly, The Geopolitical Lessons of 2020

* Thomas Pink, Suarez on Authority as Coercive Teacher

* The Impossibility of Language Acquisition, an interesting semi-interview with language research pioner Lila Geitman, was a really enjoyable look at the issues in studying language acquisition.

* Kelsey Donk looks at some of the likely effects of the shutdowns on our food supply. Briefly and roughly: most of what we have seen so far has been due simply to adjustment problems, given that we have distinct commercial and grocery food distribution systems and it is very difficult to switch from one to the other; we are not anywhere near a real shortage, since the problem is that we are actually having gluts that we can't sell because we can't distribute them to the people who are buying. These problems will slowly be solved by various sorts of improvised solutions. But food production has to be planned about a year ahead based on what we can do now; as what farmers can do now massively contracts due to distribution problems and the like, we will likely see the effects starting in February of next year. If the lockdowns don't last a long time, the problems will likely be minor disruptions in the U.S. -- milk might become very expensive, bacon might be almost impossible to get, some things might have roller coaster prices or go in and out of availability. Food distribution brownouts, so to speak. The reason they will be minor, however, is that the U.S. is a massive agricultural exporter; what is likely to happen is that we will use domestically what would usually be sold abroad. Since other exporting nations will likely do the same, nations that are less agriculturally self-sufficient -- and there are a lot -- will find their domestic production stretched very thinly. Of course, a lot depends on decisions made between now and next year as to how serious that will become.

Currently Reading

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, The Hound of the Baskervilles

Matthew C. Briel, A Greek Thomist: Providence in Gennadios Scholarios

Stephen Jarvis, Death and Mr. Pickwick

Some Poem Drafts

Sons and Daughters

I never had much to begin with.

I never knew the road to take.

All of my plans are seed ungrowing,

crumbled to dust all things I made.

I've laughed and cried

in much the way of mortal men;

I've smiled and sighed,

again, again, again.

Looking back I see an endless road

of errors made, mistakes uncaught,

with all those failures bricks in Babel

that never reached the sky I sought.

But this I know, my sons and daughters:

I fought with valiant heart and true.

Though many things I did not understand,

I did my honest best for you.

My wishes somehow turned to ashes,

my hopes would rarely bear their fruit.

So many treasures lost in shadows!

So many dreams withered at root!

I've closed my ears

to voices all around me;

I was so blind

for I did not wish to see.

When I repent, my tears well up like a river.

I took my chance on where the coins would fall,

my every deed was reckless as a gamble;

I did not win. Perhaps I lost it all.

But this I know, my sons and daughters:

though my works fade, I leave to you

the mountains, heavens, fields, and waters

which your fresh eyes may see anew.

Fragment of an Epic

Speak, O music Spirit, of the high Moon

and, bursting into legend out of life,

the ways and doings of the starward men

who rose like eagles to the argent light

and drove the black star-road to lunar lands;

of the twelve who walked, the Earth in their sky,

in deserts where no air nor water flows,

but also of those patient men who sailed

around the moon in never-ending fall

and, too, of those who aided them in flight.

Interplay

She laughed,

a dancing fountain

liquid with joy

light sunray-ballerinas

glittering in golden beam

and full of fluid smiles.

His heart

in aquiline sunrise

took wing in fiery blaze,

each feather sparking

at each exalting beat.

Story

First Day

Long Kiss

Fun Months

Wedding Bells

Crying Kids

Hard Times

Little Wins

Old Age

Final Hours

Endless Hopes

Du Fu's Spring View

the empire is fallen

mountains and rivers stand

the city is in spring

it is thick with grass and tree

one feels the time

the flowers drop tears

distressed by distance

the birds alarm the heart

the beacons are aflame

lasting for three months

a letter from home

costs ten thousand gold

my white hair

is scratched ever shorter

the whole thing soon

will not hold a hairpin

I never had much to begin with.

I never knew the road to take.

All of my plans are seed ungrowing,

crumbled to dust all things I made.

I've laughed and cried

in much the way of mortal men;

I've smiled and sighed,

again, again, again.

Looking back I see an endless road

of errors made, mistakes uncaught,

with all those failures bricks in Babel

that never reached the sky I sought.

But this I know, my sons and daughters:

I fought with valiant heart and true.

Though many things I did not understand,

I did my honest best for you.

My wishes somehow turned to ashes,

my hopes would rarely bear their fruit.

So many treasures lost in shadows!

So many dreams withered at root!

I've closed my ears

to voices all around me;

I was so blind

for I did not wish to see.

When I repent, my tears well up like a river.

I took my chance on where the coins would fall,

my every deed was reckless as a gamble;

I did not win. Perhaps I lost it all.

But this I know, my sons and daughters:

though my works fade, I leave to you

the mountains, heavens, fields, and waters

which your fresh eyes may see anew.

Fragment of an Epic

Speak, O music Spirit, of the high Moon

and, bursting into legend out of life,

the ways and doings of the starward men

who rose like eagles to the argent light

and drove the black star-road to lunar lands;

of the twelve who walked, the Earth in their sky,

in deserts where no air nor water flows,

but also of those patient men who sailed

around the moon in never-ending fall

and, too, of those who aided them in flight.

Interplay

She laughed,

a dancing fountain

liquid with joy

light sunray-ballerinas

glittering in golden beam

and full of fluid smiles.

His heart

in aquiline sunrise

took wing in fiery blaze,

each feather sparking

at each exalting beat.

Story

First Day

Long Kiss

Fun Months

Wedding Bells

Crying Kids

Hard Times

Little Wins

Old Age

Final Hours

Endless Hopes

Du Fu's Spring View

the empire is fallen

mountains and rivers stand

the city is in spring

it is thick with grass and tree

one feels the time

the flowers drop tears

distressed by distance

the birds alarm the heart

the beacons are aflame

lasting for three months

a letter from home

costs ten thousand gold

my white hair

is scratched ever shorter

the whole thing soon

will not hold a hairpin

Thursday, April 30, 2020

Osborne on Aquinas's Ethics

Thomas Osborne's Aquinas's Ethics, in the Cambridge Elements series, is available online for free until May 18. It's a pretty decent introduction to the topic. One thing I saw that I think is not quite right:

Osborne seems to be assuming that if we remove the clause, we are removing the need for divine help, but I don't think this is what Aquinas means. Aquinas is quite clear that we need divine help for all virtue, including acquired virtue. If we remove the phrase, “which God works in us without us”, from the Augustinian definition as brought together in Lombard, what we get is the genus that includes both infused and acquired virtue. The difference is really in Osborne's "caused directly by God"; or, in other words, in the "without us" part of the Augustinian definition. As he puts it (ST 2-1.55.4ad6), in acquired virtue God still works in us, but in the way in which He works in every will and nature, i.e., as first mover or remote efficient cause, not as proximate or immediate cause. But it's tricky to be precise about such a matter in a brief space, since we don't have a convenient ethical vocabulary for discussing the infused/acquired virtue distinction, so this might just be inadvertence.

The efficient cause provides some difficulty for Aquinas’s appropriation of Lombard’s definition. An efficient cause is the agent that brings about the act. According to Aquinas, Lombard’s definition identifies the efficient cause with God in the part that reads, “which God works in us without us.” Aquinas does not apply this part of the definition to an Aristotelian definition of virtue. The Christian thinkers who preceded Aquinas developed a distinction between the traditional moral virtues that are discussed by philosophers and the theological virtues, which exceed human abilities and are directly about God (Bejcvy 1990). Influenced by this tradition, Aquinas distinguishes between virtues that are described by the philosophers and those that are known and acquired through divine help. Aquinas holds that this part of the definition applies only to those Christian virtues that are caused directly by God and are described as “infused virtues.” Since they exceed natural powers, they cannot be acquired; their acts cannot be performed without divine help.

Osborne seems to be assuming that if we remove the clause, we are removing the need for divine help, but I don't think this is what Aquinas means. Aquinas is quite clear that we need divine help for all virtue, including acquired virtue. If we remove the phrase, “which God works in us without us”, from the Augustinian definition as brought together in Lombard, what we get is the genus that includes both infused and acquired virtue. The difference is really in Osborne's "caused directly by God"; or, in other words, in the "without us" part of the Augustinian definition. As he puts it (ST 2-1.55.4ad6), in acquired virtue God still works in us, but in the way in which He works in every will and nature, i.e., as first mover or remote efficient cause, not as proximate or immediate cause. But it's tricky to be precise about such a matter in a brief space, since we don't have a convenient ethical vocabulary for discussing the infused/acquired virtue distinction, so this might just be inadvertence.

Laughing Over the Gold Sunflower

Three Flower Petals

by Archibald Lampman

What saw I yesterday walking apart

In a leafy place where the cattle wait?

Something to keep for a charm in my heart--

A little sweet girl in a garden gate.

Laughing she lay in the gold sun's might,

And held for a target to shelter her,

In her little soft fingers, round and white,

The gold rimmed face of a sunflower.

Laughing she lay on the stone that stands

For a rough hewn step in that sunny place,

And her yellow hair hung down to her hands,

Shadowing over her dimpled face.

Her eyes like the blue of the sky made dim

With the might of the sun that looked at her,

Shone laughing over the serried rim,

Golden set, of the sunflower.

Laughing, for token she gave to me

Three petals out of the sunflower.

When the petals are withered and gone, shall be

Three verses of mine for praise of her,

That a tender dream of her face may rise,

And lighten me yet in another hour,

Of her sunny hair and her beautiful eyes,

Laughing over the gold sunflower.

Wednesday, April 29, 2020

A Tale of Signs and Trust

Then on the third day a wedding took place in the Galilean Cana, and the mother of Jesus was there, so Jesus and his disciples were invited to the wedding. Then, the wine having run out, the mother of Jesus says to Him, "They have no wine."

Then Jesus says to her, "What is it to me and you, ma'am? My hour is not yet."

Says His mother to the servants, "Whatever He might tell you, do."

Now there were standing there six stone water-jars for purification in the Judean style, with room for two or three metetes. Says Jesus to them, "Fill the water-jars with water." Then they filled them to the brim.

He says to them, "Draw some out and carry it to the one presiding over the feast."

And they took it, and when the one presiding had tasted it, the water having become wine and he not knowing whence it was -- though the servants knew, having drawn the water -- he calls the bridegroom and says to him, "Every man sets out the good wine at first and the worse after they have drunk freely; you have kept the good wine until now."

This Jesus did in Galilean Cana, the beginning of signs. Then He manifested His glory and His disciples trusted in Him.

After this He went down to Capernaum, He and His mother and His brothers and His disciples, and they stayed there a few days.

Then the Judean passover was near, and Jesus went up to Jerusalem. Then He found in the holy place those those selling oxen and sheep and doves, and the moneychangers were sitting down. Then, having made a whip out of ropes, He drove it all out of the holy place, the sheep and the oxen, and poured out the coins of the moneychangers, and overturned the tables. Then to those selling doves, He said, "Take these away; do not make my Father's house a mercantile house."

His disciples remember that is written: Jealousy for your house will consume me.

Thus the Judeans answered and said to Him, "What sign do you show, that you may do these things?"

Jesus answered and said to them, "Destroy this temple and in three days I will raise it."

Thus the Judeans said, "This temple was forty-six years in the building and in three days you will raise it!"

Yet He was speaking about the temple of His body. When therefore He had risen from the dead, His disciples remembered that He had said this. Then they trusted Scripture and the word Jesus had spoken.

And when He was in Jerusalem at the passover, at the festival, many trusted in His name, seeing the signs He was doing. But Jesus did not trust them, because He knew them all, and because He had no need for evidence about man, for He knew Himself what was within man.

John 2, my rough translation. I was struck by a few things. First, which I've thought before, the wedding story is rather funny. Jesus' mother essentially ignores His entirely reasonable protest, a phenomenon every mother's son has experienced at some point. And the architriclinius (presider over the feast) is quite clearly implying that the bridegroom (who can't possibly know what he's talking about) is an idiot who hadn't figured out something everyone knows.

Second, these two stories together have some interesting interplay between evidence and trust. In both the people technically in charge don't have a clue what's going on; in both it is emphasized that the disciples trusted Jesus after signs that made things obvious. And then we have the interesting bit at the end, in which many people trust Jesus because they see the signs -- in the context of a festival, the verb seems often to suggest being a spectator -- but Jesus does not reciprocate the trust because He does not need to draw His conclusions on the basis of things, like signs, that serve as evidence ('testify', as the translations usually have) -- He already knows.

The word for testifying or serving as evidence has been used before (John 1:7-8), in talking about John the Baptist, who came to serve as evidence of the Light. Later (also in the temple) he will get into an argument again with the Judeans, and says that if He gives evidence for Himself, the evidence is not true; another is giving evidence for Him and the evidence that one gives is true -- John had previously given evidence, but now His evidence is not from man but from the Father, and seen in the works He does and in Scripture. Still later (again in the temple) Jesus will identify as the Light in question (John 8:12), after which the Pharisees will attempt to turn his prior claim against Him, telling Him He is trying to serve as evidence for Himself; Jesus replies that even if that were so, such evidence can still be true because He recognizes whence He comes and whither He goes, or more exactly, He says, "I am the evidence for Myself" (John 8:18), because His Father is giving evidence in having sent Him. (Naturally, they then want to speak to his dad to get this supposed evidence.)

Much of the Gospel of John is concerned with the theme of people trying to get evidence while being completely oblivious of what's going on right in front of them; evidence keeps being given, but even the disciples don't see it until Jesus makes it obvious. But of course, immediately after the above stories from John 2, we get the discussion with Nicodemus, in which Jesus flatly says that no one can see the kingdom without being born from above. (The expression is often translated as 'reborn' or 'born again', but it's literally 'from above'. While the 'from above' was often an expression for 'again', given other things Jesus says, it is clear he does mean it literally, but Nicodemus, as if to make Jesus' point for Him, takes the 'from above' in the figurative sense, so asks how the elderly can be born.)

In John 6, the crowds are following Him because of His signs (around passover again); then He performs the miracle of feeding the five thousand. This causes Him more trouble with the crowds, and He accuses them of following Him because of the food rather than the signs; they should instead trust the one God has sent. At which point they demand that He give them a sign, like manna, so they could trust Him, as if He had not just recently done so. Jesus was right not to trust their trust, not to believe their belief. It's not an accident that John has the episode in which God literally speaks from the heavens and some of the people say it was just thunder (John 12:28-29).

Then Jesus says to her, "What is it to me and you, ma'am? My hour is not yet."

Says His mother to the servants, "Whatever He might tell you, do."

Now there were standing there six stone water-jars for purification in the Judean style, with room for two or three metetes. Says Jesus to them, "Fill the water-jars with water." Then they filled them to the brim.

He says to them, "Draw some out and carry it to the one presiding over the feast."

And they took it, and when the one presiding had tasted it, the water having become wine and he not knowing whence it was -- though the servants knew, having drawn the water -- he calls the bridegroom and says to him, "Every man sets out the good wine at first and the worse after they have drunk freely; you have kept the good wine until now."

This Jesus did in Galilean Cana, the beginning of signs. Then He manifested His glory and His disciples trusted in Him.

After this He went down to Capernaum, He and His mother and His brothers and His disciples, and they stayed there a few days.

Then the Judean passover was near, and Jesus went up to Jerusalem. Then He found in the holy place those those selling oxen and sheep and doves, and the moneychangers were sitting down. Then, having made a whip out of ropes, He drove it all out of the holy place, the sheep and the oxen, and poured out the coins of the moneychangers, and overturned the tables. Then to those selling doves, He said, "Take these away; do not make my Father's house a mercantile house."

His disciples remember that is written: Jealousy for your house will consume me.

Thus the Judeans answered and said to Him, "What sign do you show, that you may do these things?"

Jesus answered and said to them, "Destroy this temple and in three days I will raise it."

Thus the Judeans said, "This temple was forty-six years in the building and in three days you will raise it!"

Yet He was speaking about the temple of His body. When therefore He had risen from the dead, His disciples remembered that He had said this. Then they trusted Scripture and the word Jesus had spoken.

And when He was in Jerusalem at the passover, at the festival, many trusted in His name, seeing the signs He was doing. But Jesus did not trust them, because He knew them all, and because He had no need for evidence about man, for He knew Himself what was within man.

John 2, my rough translation. I was struck by a few things. First, which I've thought before, the wedding story is rather funny. Jesus' mother essentially ignores His entirely reasonable protest, a phenomenon every mother's son has experienced at some point. And the architriclinius (presider over the feast) is quite clearly implying that the bridegroom (who can't possibly know what he's talking about) is an idiot who hadn't figured out something everyone knows.

Second, these two stories together have some interesting interplay between evidence and trust. In both the people technically in charge don't have a clue what's going on; in both it is emphasized that the disciples trusted Jesus after signs that made things obvious. And then we have the interesting bit at the end, in which many people trust Jesus because they see the signs -- in the context of a festival, the verb seems often to suggest being a spectator -- but Jesus does not reciprocate the trust because He does not need to draw His conclusions on the basis of things, like signs, that serve as evidence ('testify', as the translations usually have) -- He already knows.

The word for testifying or serving as evidence has been used before (John 1:7-8), in talking about John the Baptist, who came to serve as evidence of the Light. Later (also in the temple) he will get into an argument again with the Judeans, and says that if He gives evidence for Himself, the evidence is not true; another is giving evidence for Him and the evidence that one gives is true -- John had previously given evidence, but now His evidence is not from man but from the Father, and seen in the works He does and in Scripture. Still later (again in the temple) Jesus will identify as the Light in question (John 8:12), after which the Pharisees will attempt to turn his prior claim against Him, telling Him He is trying to serve as evidence for Himself; Jesus replies that even if that were so, such evidence can still be true because He recognizes whence He comes and whither He goes, or more exactly, He says, "I am the evidence for Myself" (John 8:18), because His Father is giving evidence in having sent Him. (Naturally, they then want to speak to his dad to get this supposed evidence.)

Much of the Gospel of John is concerned with the theme of people trying to get evidence while being completely oblivious of what's going on right in front of them; evidence keeps being given, but even the disciples don't see it until Jesus makes it obvious. But of course, immediately after the above stories from John 2, we get the discussion with Nicodemus, in which Jesus flatly says that no one can see the kingdom without being born from above. (The expression is often translated as 'reborn' or 'born again', but it's literally 'from above'. While the 'from above' was often an expression for 'again', given other things Jesus says, it is clear he does mean it literally, but Nicodemus, as if to make Jesus' point for Him, takes the 'from above' in the figurative sense, so asks how the elderly can be born.)

In John 6, the crowds are following Him because of His signs (around passover again); then He performs the miracle of feeding the five thousand. This causes Him more trouble with the crowds, and He accuses them of following Him because of the food rather than the signs; they should instead trust the one God has sent. At which point they demand that He give them a sign, like manna, so they could trust Him, as if He had not just recently done so. Jesus was right not to trust their trust, not to believe their belief. It's not an accident that John has the episode in which God literally speaks from the heavens and some of the people say it was just thunder (John 12:28-29).

Doctor Providentiae

Today is the feast of St. Caterina di Giacomo di Benincasa, better known as St. Catherine of Siena, Doctor of the Church. She was the twenty-fourth of twenty-five children. From a letter to her brother, whose name seems to have been Benincasa di Benincasa:

From her most influential work, The Dialogue:

The 'another Himself' phrase is, of course, an allusion to the common saying that a friend is another self.

Dearest brother in Christ Jesus: I Catherine, a useless servant, comfort and bless thee and invite thee to a sweet and most holy patience, for without patience we could not please God. So I beg you, in order that you may receive the fruit of your tribulations, that you assume the armour of patience. And should it seem very hard to you to endure your many troubles, bear in memory three things, that you may endure more patiently. First, I want you to think of the shortness of your time, for on one day you are not certain of the morrow. We may truly say that we do not feel past trouble, nor that which is to come, but only the moment of time at which we are. Surely, then, we ought to endure patiently, since the time is so short. The second thing is, for you to consider the fruit which follows our troubles. For St. Paul says there is no comparison between our troubles and the fruit and reward of supernal glory. The third is, for you to consider the loss which results to those who endure in wrath and impatience; for loss follows this here, and eternal punishment to the soul.

From her most influential work, The Dialogue:

The soul, who is lifted by a very great and yearning desire for the honor of God and the salvation of souls, begins by exercising herself, for a certain space of time, in the ordinary virtues, remaining in the cell of self-knowledge, in order to know better the goodness of God towards her. This she does because knowledge must precede love, and only when she has attained love, can she strive to follow and to clothe herself with the truth. But, in no way, does the creature receive such a taste of the truth, or so brilliant a light therefrom, as by means of humble and continuous prayer, founded on knowledge of herself and of God; because prayer, exercising her in the above way, unites with God the soul that follows the footprints of Christ Crucified, and thus, by desire and affection, and union of love, makes her another Himself. Christ would seem to have meant this, when He said: To him who will love Me and will observe My commandment, will I manifest Myself; and he shall be one thing with Me and I with him.

The 'another Himself' phrase is, of course, an allusion to the common saying that a friend is another self.

Tuesday, April 28, 2020

A Mousetrap for the Devil

The Devil exulted when Christ died, and by that very death of Christ the Devil was overcome: he took food, as it were, from a trap. He gloated over the death as if he were appointed a deputy of death; that in which he rejoiced became a prison for him. The cross of our Lord became a trap for the Devil; the death of the Lord was the food by which he was ensnared.

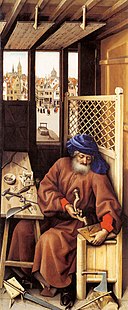

This passage, from one of St. Augustine's Ascension sermons, has had an interesting history. The translation above, which I take it is Sister Mary Sarah Muldowney's, is a very sober translation, but you can easily translate this more flamboyantly. The word for 'trap' here is muscipula, which literally means a mousetrap. And the image of the Cross as a mousetrap for the devil, the theme of muscipula diaboli, crux Christi, is one that you find in a number of places. One of the more famous is the Mérode Altarpiece, which has St. Joseph making mousetraps while the Annunciation is going on (you can click through for a better view):

In reality, while the word does literally and etymologically mean 'mousetrap', it had become a very common word for all kinds of traps. If you read a lot of Augustine, you know that he usually doesn't invent things like this, although he will sometimes employ them creativity; the image actually comes from Scripture. The Latin of the Psalter Augustine knew uses muscipula a lot for any kind of hunting snare; for instance, in Psalm 124:7 (or 123:7 in the old numbering) it is used for a bird-snare: "We have escaped like a bird from the fowler’s snare; the snare has been broken, and we have escaped." It's the common Scriptural image of the wicked laying a snare for others; and as in Psalm 9:16, it is sometimes presented as the wicked falling into their own snare. And this, of course, is something like Augustine's idea, which he mentions explicitly earlier in the sermon:

But if He had not been put to death, death would have not died. The Devil was overcome by his own trophy, for the Devil rejoiced when, by seducing the first man, he cast him into death. By seducing the first man, he killed him; by killing the last Man, he lost the first from his snare.

Probably the most accurate translation for it would be 'pitfall', i.e., a trap consisting of a baited hole in the ground; Adam is thrown into the pit (death) and throwing Adam into the pit (bringing death upon humanity) leads to throwing Christ into the pit (Christ as man also dies on the Cross); but Christ rises and ascends out of the pit (Resurrection and Ascension), bringing Adam with him. And because of it, the Devil himself is toppled into a pit (hell, the second death) because he was greedy for the bait (death for all human beings, which includes Christ).

But the mousetrap makes for a very vivid image.

Sunday, April 26, 2020

Fortnightly Book, April 26

There should be no combination of events for which the wit of man cannot conceive an explanation.

The next fortnightly books will be Sir Arthur Conan Doyle's most popular Holmes novel and his least read Holmes novel, The Hound of the Baskervilles and The Valley of Fear.

Hound, which is widely regarded as one of the great detective stories of all time, was serialized in The Strand Magazine in 1901 and 1902. Benefiting from the extraordinary success of the Holmes short stories and building on Doyle's strengths and interests, unleashed on a public that was hungry for more Holmes after Doyle had killed him off eight years earlier, it took the world by storm, and its success was what convinced Doyle to try to write more Sherlock Holmes tales.

Valley, which is the Holmes novel people are least likely to have read, was serialised in The Strand Magazine in 1914 and 1915. As with his first two novels, Doyle combines Holmesian detection with an exotic foreign locale, this time the strange and wild land of Pennsylvania, where coal miners are legion and struggles between miners and owners have come to a boiling point, with the latter bringing in the Pinkertons. However, there's more here than meets the idea; offstage, in the shadows, Professor Moriarty is spinning a complicated and dangerous web. Despite everyone knowing Moriarty as his witness, this is the only story other than "The Final Problem" in which Moriarty is definitely involved (although Moriarty is mentioned briefly in five other late stories). Indeed, part of Valley's purpose seems to be to fill in a bit of the backstory about the enmity between Holmes and Moriarty.

While both Hound and Valley are written after Holmes's death in "The Final Problem", they are both a return to the pre-death Holmes. (Valley, in fact, creates one of the well-known puzzles for enthusiasts of the Great Game, since in "The Final Problem" Watson seems to be completely ignorant of Moriarty, whereas here, despite the story being set earlier, Watson knows him very well.

Charles Dickens, The Pickwick Papers

Introduction

Opening Passage:

Summary: Samuel Pickwick was a very successful businessman who has retired; like many who retire, he has to manufacture something to occupy his time, which he does by getting together with friends. This is the origin of The Pickwick Club, whose reason for being is to uncover and tell quaint and curious stories from all over. A good-natured, generous individual driven by interest in the curious and peculiar will inevitably have some difficulty with others taking advantage, so Pickwick ends up in a wide variety of complicated situations, including at one point getting sued for breach of promise due to the cunning machinations of some slippery lawyers and ending up in debtor's prison, despite being extraordinarily rich, because he refuses to give a penny to such dishonest lawyers.

The primary mode of storytelling here is episodic, and thus is character-driven rather than plot-driven. Since it draws on comedy conventions, courting and marriage come up a lot. Besides Pickwick, we follow his three close friends (the Pickwickians) and his manservant.

(1) Nathaniel Winkle: Winkle is the only remnant of the original proposal of comic stories about a sporting club; he is a sporting enthusiast but also consistently inept with a gun. He has a flirtatious relationship with Arabella Allen.

(2) Augustus Snodgrass: A poet who never finishes any poetry, he tries to marry Emily Wardle.

(3) Tracy Tupman: A good-natured, fat, middle-aged man who thinks of himself has something of a ladies' man, he gets outmaneuvered in his attempt to marry Rachael Wardle (Emily's spinster aunt) by a smooth-talking con artist, Alfred Jingle.

(4) Samuel Weller: A clever, cockney all-purpose handyman, Weller is hired by Pickwick early on as a manservant, and becomes central to helping Pickwick get out of his scrapes. He is actually what Tupman thinks of himself as being, and one of the key questions of his storyline is whether his flirtation with the pretty maid Mary (who is essential to getting Winkle and Arabella together) will ever amount to more than a flirtation.

To the extent that there is a unified story, it is structured by the indirect battle between the Pickwickians and their nemeses, Alfred Jingle and his manservant Job Trotter. Jingle and Pickwick are equal-and-opposite; their courses of life parallel each other almost exactly, but their personalities take them in different directions. Since Pickwick is innocent and inclined to give people the benefit of the doubt, and Jingle is cunning and always scheming for advantage, Jingle generally has the upper hand when they cross paths, and, as you might expect, a key issue in the story is how Pickwick's innocent goodwill toward people will win out over the apparent advantages of Jingle's machinations.

The Pickwick Papers is very much about friendship, and I suspect one element in its enduring popularity is how well Dickens captures the combination of the absurd and the admirable that so often constitutes friendship-adventures that become stories worth telling, combined with his talent for exaggerating to comic effect. The episodic nature of the story, combined with its length, makes it the sort of book, however, that's probably best taken in small portions. We forget that these big nineteenth-century books weren't usually written to be read altogether but as serials; this is certainly true of The Pickwick Papers. Trying to read it all at once is a bit like trying to marathon through four or five seasons' worth of sitcom episodes. Repetitions that are charming recurring jokes when partaking serially can become merely repetitive in the marathon; details that are striking and enjoyable in serial can start blurring into the background in marathon; goofiness in small sips becomes a bit much in vast quantities; and so forth. With Dickens's skill, you still get something worth reading in large gulps, but it's still a work designed to be taken by the shot glass rather than by the beer stein.

Some of the most interesting parts of the book, in my opinion, were the occasional digressions, as the Pickwickians come across characters with their own odd stories, giving us a digression and a bit of a rest from the Pickwickian humor. "The Stroller's Tale" (Chapter 3), "The Story of the Goblins Who Stole a Sexton" (Chapter 29), and "The Story of the Bagman's Uncle" (Chapter 49) are all excellent short stories in their own right. The Christmas chapters (Chapter 28 and following) were enjoyable as well, since Dickens really pulls out the descriptive stops, and Dickens is hilariously funny whenever lawyers are involved. I particularly appreciated Serjeant Buzfuz's attempt to argue that Pickwick had obviously been leading Mrs. Bardell on, given a note that said "Dear Mrs. B.—Chops and tomata sauce", since 'chops' and 'tomata sauce' could only be interpreted as affectionate nicknames, as well as the cunning with which Mrs. Bardell's lawyers establish the truth of the proverb that, come what may, the lawyers get their pay.

I also listened to the Mercury Theater on the Air's radio adaptation of The Pickwick Papers, which can be found here, here (#18), and here. It's quite faithful, since the episodic narrative means you can select which episodic events to use, but it likewise shows some of the difficulties of adapting the episodic narrative -- things just kind of go in random directions. It's really obvious, though, that the actors were enjoying themselves (the exaggerated features of Dickensian characters give radio actors a lot to work with, especially in a story like this that differentiates the characters by manner of speech) and once we get a coherent stretch, namely the breach of promise trial, things start picking up. Welles unsurprisingly plays a fast-talking Mr. Jingle, but given the structure of the work and the limits of adaptation, there's much less of him than you'd expect.

Favorite Passage:

Recommendation: Highly Recommended, although, again, you should probably take it in small portions.

Opening Passage:

The first ray of light which illumines the gloom, and converts into a dazzling brilliancy that obscurity in which the earlier history of the public career of the immortal Pickwick would appear to be involved, is derived from the perusal of the following entry in the Transactions of the Pickwick Club, which the editor of these papers feels the highest pleasure in laying before his readers, as a proof of the careful attention, indefatigable assiduity, and nice discrimination, with which his search among the multifarious documents confided to him has been conducted.

Summary: Samuel Pickwick was a very successful businessman who has retired; like many who retire, he has to manufacture something to occupy his time, which he does by getting together with friends. This is the origin of The Pickwick Club, whose reason for being is to uncover and tell quaint and curious stories from all over. A good-natured, generous individual driven by interest in the curious and peculiar will inevitably have some difficulty with others taking advantage, so Pickwick ends up in a wide variety of complicated situations, including at one point getting sued for breach of promise due to the cunning machinations of some slippery lawyers and ending up in debtor's prison, despite being extraordinarily rich, because he refuses to give a penny to such dishonest lawyers.

The primary mode of storytelling here is episodic, and thus is character-driven rather than plot-driven. Since it draws on comedy conventions, courting and marriage come up a lot. Besides Pickwick, we follow his three close friends (the Pickwickians) and his manservant.

(1) Nathaniel Winkle: Winkle is the only remnant of the original proposal of comic stories about a sporting club; he is a sporting enthusiast but also consistently inept with a gun. He has a flirtatious relationship with Arabella Allen.

(2) Augustus Snodgrass: A poet who never finishes any poetry, he tries to marry Emily Wardle.

(3) Tracy Tupman: A good-natured, fat, middle-aged man who thinks of himself has something of a ladies' man, he gets outmaneuvered in his attempt to marry Rachael Wardle (Emily's spinster aunt) by a smooth-talking con artist, Alfred Jingle.

(4) Samuel Weller: A clever, cockney all-purpose handyman, Weller is hired by Pickwick early on as a manservant, and becomes central to helping Pickwick get out of his scrapes. He is actually what Tupman thinks of himself as being, and one of the key questions of his storyline is whether his flirtation with the pretty maid Mary (who is essential to getting Winkle and Arabella together) will ever amount to more than a flirtation.

To the extent that there is a unified story, it is structured by the indirect battle between the Pickwickians and their nemeses, Alfred Jingle and his manservant Job Trotter. Jingle and Pickwick are equal-and-opposite; their courses of life parallel each other almost exactly, but their personalities take them in different directions. Since Pickwick is innocent and inclined to give people the benefit of the doubt, and Jingle is cunning and always scheming for advantage, Jingle generally has the upper hand when they cross paths, and, as you might expect, a key issue in the story is how Pickwick's innocent goodwill toward people will win out over the apparent advantages of Jingle's machinations.

The Pickwick Papers is very much about friendship, and I suspect one element in its enduring popularity is how well Dickens captures the combination of the absurd and the admirable that so often constitutes friendship-adventures that become stories worth telling, combined with his talent for exaggerating to comic effect. The episodic nature of the story, combined with its length, makes it the sort of book, however, that's probably best taken in small portions. We forget that these big nineteenth-century books weren't usually written to be read altogether but as serials; this is certainly true of The Pickwick Papers. Trying to read it all at once is a bit like trying to marathon through four or five seasons' worth of sitcom episodes. Repetitions that are charming recurring jokes when partaking serially can become merely repetitive in the marathon; details that are striking and enjoyable in serial can start blurring into the background in marathon; goofiness in small sips becomes a bit much in vast quantities; and so forth. With Dickens's skill, you still get something worth reading in large gulps, but it's still a work designed to be taken by the shot glass rather than by the beer stein.

Some of the most interesting parts of the book, in my opinion, were the occasional digressions, as the Pickwickians come across characters with their own odd stories, giving us a digression and a bit of a rest from the Pickwickian humor. "The Stroller's Tale" (Chapter 3), "The Story of the Goblins Who Stole a Sexton" (Chapter 29), and "The Story of the Bagman's Uncle" (Chapter 49) are all excellent short stories in their own right. The Christmas chapters (Chapter 28 and following) were enjoyable as well, since Dickens really pulls out the descriptive stops, and Dickens is hilariously funny whenever lawyers are involved. I particularly appreciated Serjeant Buzfuz's attempt to argue that Pickwick had obviously been leading Mrs. Bardell on, given a note that said "Dear Mrs. B.—Chops and tomata sauce", since 'chops' and 'tomata sauce' could only be interpreted as affectionate nicknames, as well as the cunning with which Mrs. Bardell's lawyers establish the truth of the proverb that, come what may, the lawyers get their pay.

I also listened to the Mercury Theater on the Air's radio adaptation of The Pickwick Papers, which can be found here, here (#18), and here. It's quite faithful, since the episodic narrative means you can select which episodic events to use, but it likewise shows some of the difficulties of adapting the episodic narrative -- things just kind of go in random directions. It's really obvious, though, that the actors were enjoying themselves (the exaggerated features of Dickensian characters give radio actors a lot to work with, especially in a story like this that differentiates the characters by manner of speech) and once we get a coherent stretch, namely the breach of promise trial, things start picking up. Welles unsurprisingly plays a fast-talking Mr. Jingle, but given the structure of the work and the limits of adaptation, there's much less of him than you'd expect.

Favorite Passage:

‘An abstruse subject, I should conceive,’ said Mr. Pickwick.

‘Very, Sir,’ responded Pott, looking intensely sage. ‘He crammed for it, to use a technical but expressive term; he read up for the subject, at my desire, in the “Encyclopaedia Britannica.”’

‘Indeed!’ said Mr. Pickwick; ‘I was not aware that that valuable work contained any information respecting Chinese metaphysics.’

‘He read, Sir,’ rejoined Pott, laying his hand on Mr. Pickwick’s knee, and looking round with a smile of intellectual superiority—‘he read for metaphysics under the letter M, and for China under the letter C, and combined his information, Sir!’

Recommendation: Highly Recommended, although, again, you should probably take it in small portions.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)