The approach to the castle was a bit of a mess, since they were doing construction for the Edinburgh Military Tattoo.

As you get to the gate, you can see the well-known statues representing Robert the Bruce (left) and William Wallace (right). You also get the Scottish motto, Nemo me impune lacessit, or, as the Scots translate it, Wha daur meddle wi' me?

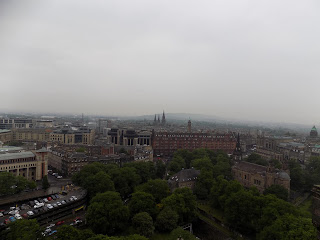

The castle grounds themselves are not very intuitively laid out, and everybody just mills wherever, so it's not straightforward to find anything. But the views are very nice.

They have a cemeteries for dogs that have been adopted by the regiments in one way or another:

There is Mons Meg, the massive cannon built in the fifteenth century by King Philip the Good of France and gifted to James II, King of Scots. It is one of the largest cannons ever made. It was seized by the English in 1754 and only returned to Scotland by the persuasion of Sir Walter Scott. I couldn't get a good picture of it because everyone was always crowded around it, so here's one from Wikimedia Commons:

The most important building on the castle grounds is St. Margaret's Chapel, generally thought to be the oldest building in Edinburgh. Queen St. Margaret was the wife of King Malcolm from 1070 to 1093; she died at Edinburgh Castle, which at the time was the royal palace. The chapel was built by her youngest son, King David I, and stands on the highest point of the castle grounds. It is currently freestanding, although there is evidence from the masonry that it was at one time probably connected to another building on one side.

It ceased to be used more than occasionally when the royal living quarters were moved from Edinburgh Castle to Holyrood Palace in the 1530s, and in the Scottish Reformation it was turned into a gunpowder shed, which it continued to be until restoration began under Queen Victoria. Now it is a working chapel again, although mostly for things like weddings. It holds about twenty people.

There's also a nice equestrian statue of Sir Douglas Haig, Expeditionary Commander of the Western Front in World War I. The Castle is a great place if you are interested in military history; essentially, it functions as a military history museum, more than anything. I didn't take very many pictures of the exhibits, in part because they were usually quite dark and it's best not to use flash in museums.

After the Castle, we headed north. Along the way I caught a quick picture of a plaque commemorating the birthplace of Alexander Graham Bell. (The building is offices now, so there isn't anything there except the plaque.)

Our destination in going north was The Georgian House in New Town. In the eighteenth century, Edinburgh was in fairly bad shape. As I previously mentioned, Edinburgh's growth pattern was unusual because the fights with the English led to its confinement within its medieval walls much longer than was usually the case elsewhere, and its burgeoning population did not spread out. In the middle of the 1700s, there were about 70,000 people crammed into the long 143 acres of Old Town. (For reference, Vatican City State is about 108 acres and the National Mall in Washington DC is about 309 acres. There are about 11,000 residents of Old Town today.) The buildings throughout Old Town are noticeably very tall, rarely less than five stories, and this is not a new thing. Twelve large families might share one building. The inevitable problems of crowding were very acute. The city had a good supply of water, but no plumbing; it all had to be carried by water caddies (usually elderly women in need of a wage) up flights of stairs. Sanitation was as awful as you could imagine -- hence the city's nickname of Auld Reekie. The North Loch was noxious and swampy and full of sewage. The Union, however, gave a breathing space, and in the eighteenth century the North Loch was, in stages, drained and turned into a canal of running water rather than a stagnant marsh-lake. The idea was hatched to build, from scratch a New Town to serve as a residential area, an entirely planned town. A design competition in the 1760s led to James Craig being the architect in charge.

The New Town design also let Edinburgh do an elaborate bit of sucking-up to the English after the Jacobite Rebellions. Its main thoroughfares were George (named after the King, George III), Queen, and Prince Streets. The roads linked St. Andrew's Square and St. George's Square, after the patron saints of Scotland and England. (St. George's Square was later changed to Charlotte Square -- named after the Queen -- to avoid confusion with another George's Square.) Two important secondary streets were called Rose Street and Thistle Street, for the floral symbols of England and Scotland. The buildings were done in strict Georgian style -- indeed, while the individual buildings were often admired, the New Town itself was often criticized for being boring and repetitive. But it became the place to live if you were at all high society.

The Georgian House is actually No. 7 Charlotte Square. Being on Charlotte's Square itself, it was for the cream of the cream; only St. Andrew's Square was a more impressive address. Charlotte's Square (the statue is Prince Albert and dates from the 1870s):

The basic layout is that there are several houses together, but they are fronted in such a way that the whole thing looks like a massive palace:

No. 7 was first bought by John Lamont, Chief of Clan Lamont. He moved in in 1796. The Lamonts had the residence until they sold it in 1817 to Catherine Farquharson of Invercauld, a wealthy widow. She was in the house until 1845, when it was bought by Lord Neaves, a who lived there until 1889, when The Reverend and Mrs. Alexander Whyte bought it. In 1927, it was bought by the Marquess of Bute, who had bought No. 5 and No. 6, as well. (No. 6, Bute House, is today the official residence of the First Minister of Scotland.) In 1966, it passed into the hands of the National Trust for Scotland, who restored it as an eighteenth century residence, and it became The Georgian House. Since I'm a member of the National Trust for Scotland USA, I got in free. It's a fairly well done museum; I would certainly recommend it to anyone visiting Edinburgh with children, because it has all sorts of little activities to keep kids interested -- you can even dress up in period costumes, if you like. The volunteers in each room were overflowing with information about details like the furniture; most of which, I'm afraid, was a bit lost on me. But it was interesting to get an overall sense of how the well-to-do lived in the period.

One of the best views in New Town is the intersection of George Street and Castle Street. Looking one way we see Thomas Chalmers, the theologian, philosopher, and political economist most famous for his Bridgewater Treatise, On the Power, Wisdom and Goodness of God as Manifested in the Adaptation of External Nature to the Moral and Intellectual Constitution of Man:

And in the other direction you see the Castle:

And that more or less finished our day and the bulk of what we did in Edinburgh itself.

to be continued